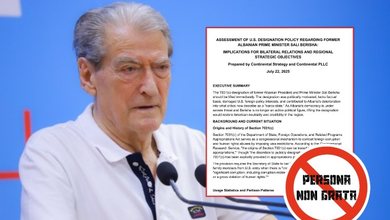

Senior officials currently accused of corruption, such as former Prime Minister Sali Berisha, former President Ilir Meta, or the Mayor of Tirana, Erion Veliaj, are expected to receive significantly lower sentences if a draft for a new Criminal Code proposed by the government as "the work of experts" is approved in parliament, provided they are not found innocent during the trial.

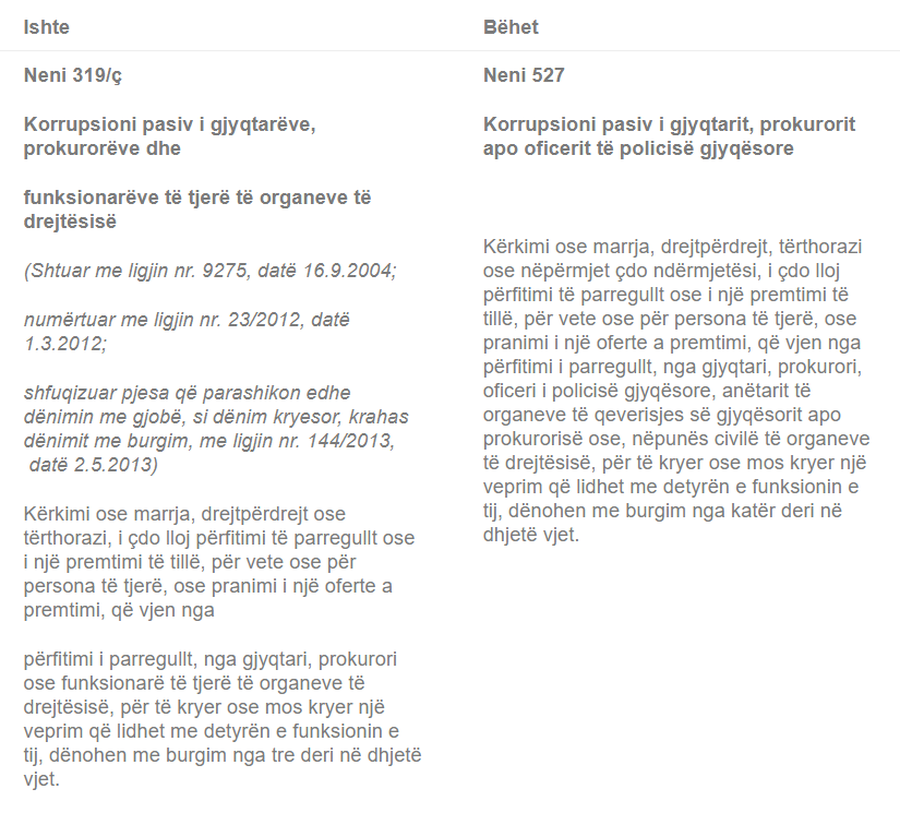

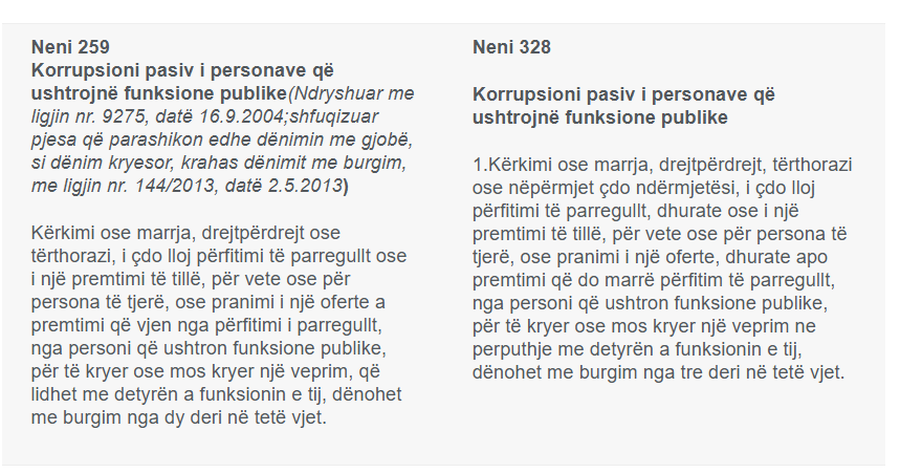

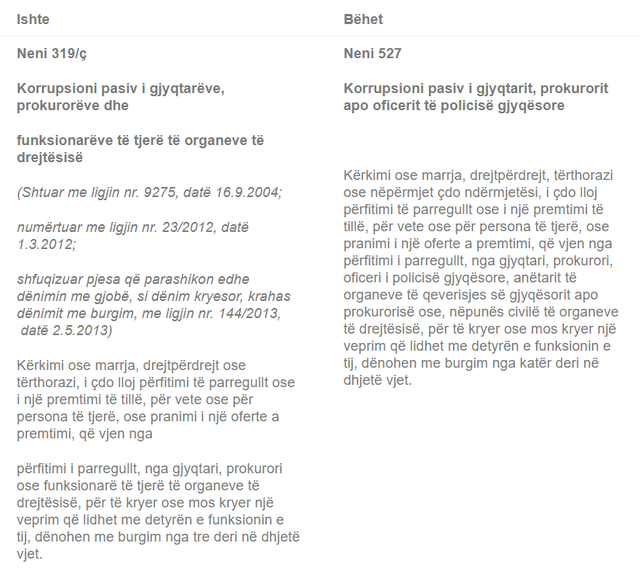

The drafters of the new Criminal Code, who have not come out to publicly defend their work to date, appear to have combined into one criminal offense what in the current criminal code is divided into two separate articles, passive corruption of officials.

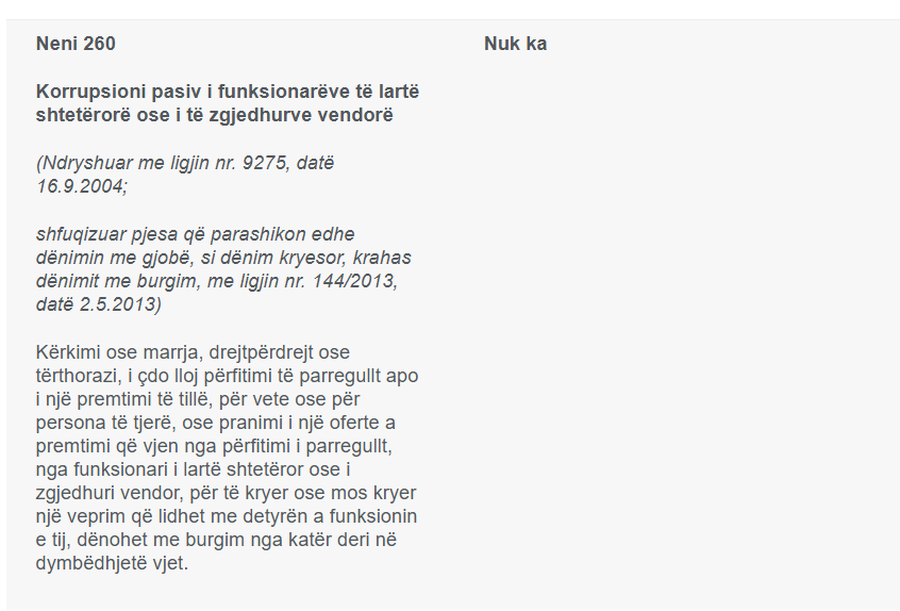

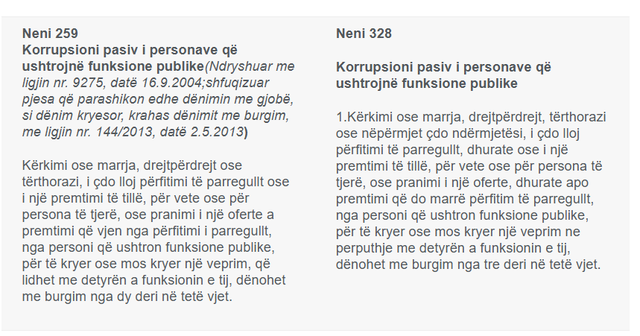

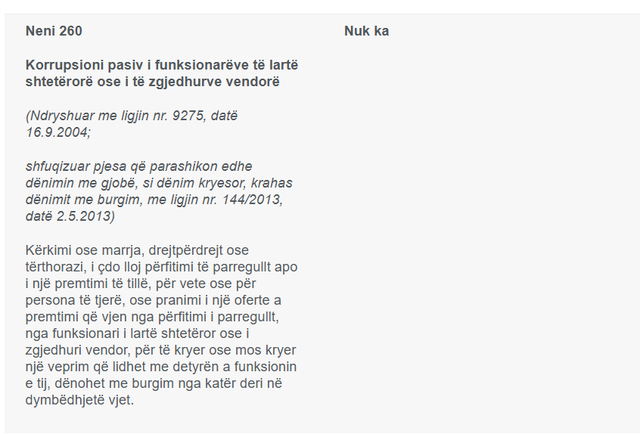

The current Code punishes cases of bribery of ordinary public officials in Article 259 with 2 to 8 years in prison, while corruption of high-ranking state officials or local elected officials is punished in Article 260 with four to twelve years in prison. In contrast, the new Criminal Code provides for the punishment of corruption for all officials, regardless of level, from three to eight years in prison.

The reduction of the minimum sentence from four to three, and the maximum sentence from twelve to eight, seems to be in contradiction with the general aggravating tendency of the draft code, which has been criticized so far mostly for increasing the sentence for many criminal offenses or misdemeanors, without any justification for the needs or costs and benefits.

While the violation of the symbols of the Republic is considered in the current Code a misdemeanor punishable by a fine of up to three months in prison, in the new Code it is punishable by up to 4 years in prison, in addition to the massive expansion of the scope of action compared to the current article. But unlike the general aggravating trend, which the head of the Bar Association, Maks Haxhia, described as being from “inquisitors”, the drafters have seen fit to equate the corruption of high-ranking officials with that of ordinary officials and, consequently, to reduce the punishment.

De facto amnesty?

The Criminal Code of a country, in addition to providing for criminal offenses or misdemeanors, also carries the concept that a criminal offense cannot be tried and punished beyond a reasonable period from the time of its commission. The statute of limitations, as it is technically known, depends on the gravity of the criminal offense. If a criminal offense provides for a low penalty, its statute of limitations is also low, while for serious criminal offenses, the statute of limitations is longer. For example, crimes against humanity or war crimes are not subject to statute of limitations; they are prosecuted and punished regardless of the period that has passed since their commission, provided that the suspect is alive.

Reducing the punishment for corruption of high-ranking officials by equating them with ordinary officials consequently leads to a reduction in the statute of limitations for this criminal offense, suggesting that some high-ranking officials, currently under indictment, may be amnestied.

The current Criminal Code stipulates in Article 66 that for criminal offenses that provide for a sentence of no less than ten years, the statute of limitations is twenty years, while for those where the sentence is from five to ten years, the statute of limitations is ten years. The new draft code does not differ much from the old one except for the form. Here, the statute of limitations is noted in Article 185. In point c it is written: “ten years for crimes that provide for a sentence of over five to ten years of imprisonment”. Consequently, a corruption offense that was committed before 2015 is, according to this code, statute of limitations. /BIRN/