School closures and collective classes are compromising the quality of basic education for a generation of students living in rural areas, experts warn.

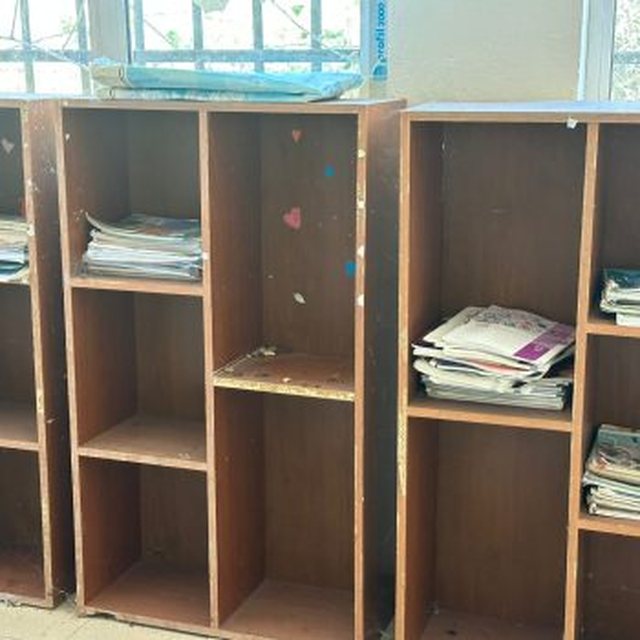

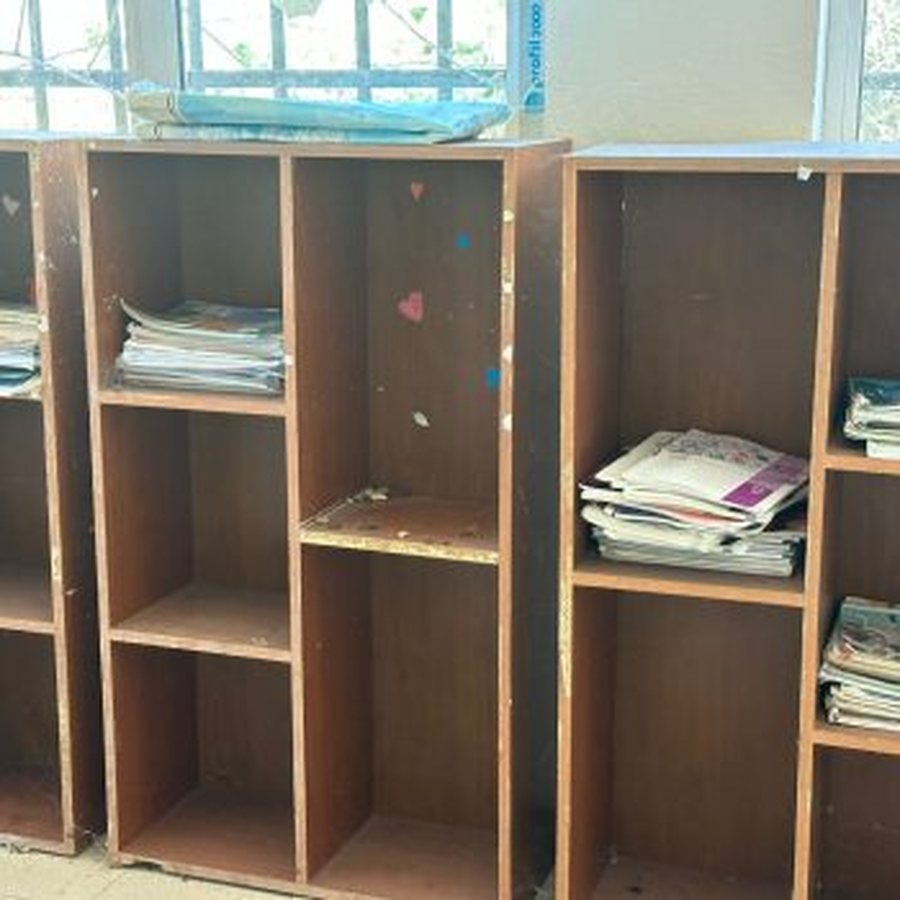

The 9-year-old school “Mark Pal Kola” in Vig remains open, but silent. For three years, neither the hum of children, nor the voices of teachers, nor the ringing of the clock have been heard. The desks remain filled with books and notebooks left behind, the class registers still lie on the table – as if the lesson had only ended yesterday.

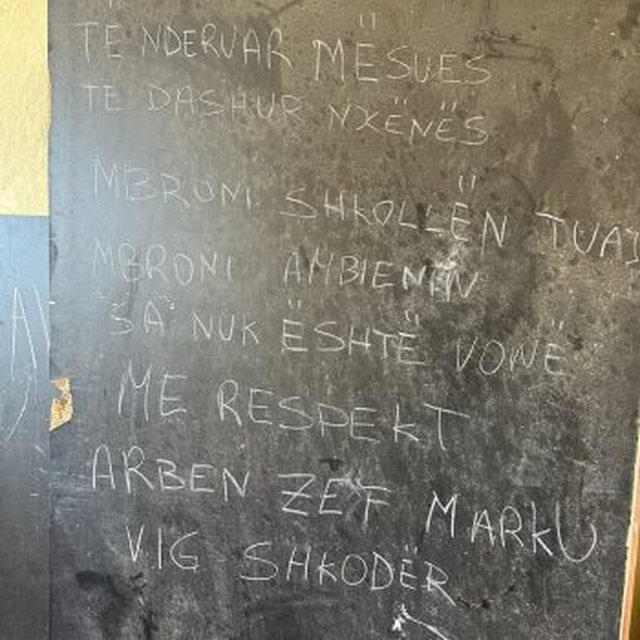

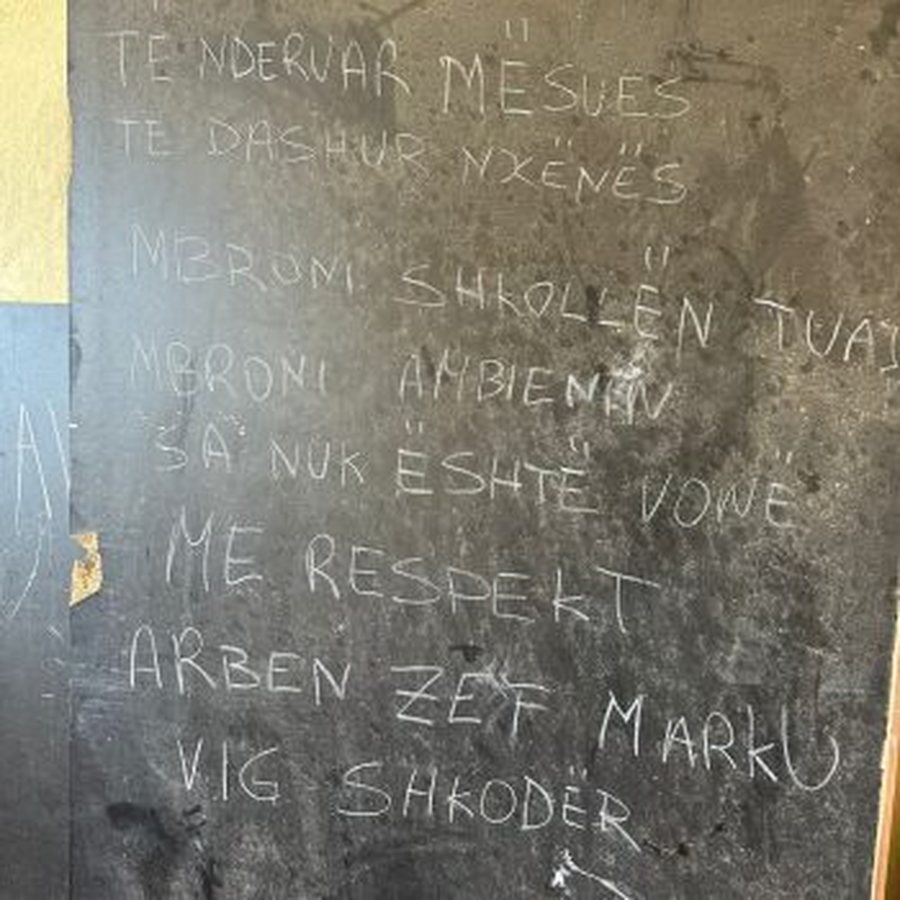

But the building has long been abandoned, while the few students in the area are forced to travel 15 kilometers every day to schools in Vau i Dejës. On the blackboard, a call left by a former student tries to give voice to a void that grows year after year: “Protect your school before it’s too late.”

Vigu is no exception. In the last two years alone, 149 rural schools across the country have closed their doors due to a lack of students, due to emigration, an aging population and a lack of long-term investment in education. Experts warn that this is no longer a matter of sporadic statistics, but of a deep structural crisis.

"The biggest problem today is the very way the education system has been built," said Irsa Ruçi, an expert on pre-university education, adding that its essence has not been interfered with for decades.

"The problems we see are a facade; the system needs to be changed at its roots," she emphasized.

In the southeast, history repeats itself. The 9-year-old school in Polena did not open its doors to its students this year. Unlike Vigu, Polena is a lively village near Korça, known for its festivals that draw thousands of visitors each summer. But the residents who have remained during the year are mostly elderly and there are so few children that they were not enough to keep the school open.

The schoolyard is overrun with chickens and piles of construction materials, which residents say will be used for a new project. The building could be turned into a hotel, they say in a low voice, not wanting to be on camera. Instead of the children's voices that once filled the hallways, two structures have been erected inside for the preparation of winter delicacies – petka, rosnicka, trahana, oshafka, jam and others, an ancient tradition of the village housewives, which has now found shelter in the former building of knowledge.

In Kolanec, Maliqi, the school was also closed this year, and the five children from the village commute to the city by car every day. The schools in Tërovë, Pendavinj and Fshat-Maliqi have also suffered the same fate.

But school closures are only one side of the problem. The significant increase in the number of students in group classes is further aggravating the situation.

“We had about 22,000 students in collective classes, now we have 30,000,” says teacher Ndriçim Mehmeti. “In such classes, there can be no quality of teaching and the motivation of teachers and students also drops,” he added.

According to Mehmeti, the Albanian education system is in urgent need of investment.

"Find opportunities, you have opportunities, take advantage of opportunities and if not then we will continue to have these achievements in PISA, in all international exams and as a result students will find salvation only by fleeing abroad, or by congregating in large urban areas," he said.

The PISA test is a worldwide initiative by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD, to measure the ability of 15-year-old students to use their knowledge in mathematics, science and reading. In the latest report published on the testing of Albanian students, in December 2024, Albania recorded a decline in all three test areas, being classified as a “negative anomaly”.

“I believe it is the desire of everyone in this country to see schoolyards buzzing,” said Irsa Ruçi. “But it is unfortunate that the centers of knowledge are closing,” she concluded./BIRN/