Albanian families in southern Serbia are feeling a new wave of anxiety: the possible return of compulsory military service in Serbia is bringing back the fears of the 1980s and 1990s.

When Sadik Sadiku from Rahovice e Presevo, in southern Serbia, hears the word “army,” he doesn’t think of defense, but of hermetically sealed coffins that brought pain to his family.

Forty-three years ago, his nephew, Yzeiri, returned dead from military service in the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA). His body arrived home in a sealed coffin – without the family being able to open it and see it. Military authorities at the time described the case as a “suicide,” saying the young man had thrown himself from a high building. But the family never accepted this version. The circumstances raised suspicions of abuse or even murder.

Today, the warnings of the Serbian authorities about the return of compulsory military service have brought back Sadik's old fears. The return of military service and the concern of the Albanian community

A week ago, the Chief of the General Staff of the Serbian Army, Milan Mojsilović, declared that the country has not given up on the return of compulsory military service, which was abolished in 2011.

Serbian President, Aleksandar Vučić, announced in September last year that he had approved the return of this service, which would last 75 days.

Serbian Defense Minister Bratislav Gasic said on September 19 that the first generation could begin compulsory military service early next year. He said he expects a new package of laws on the army to be considered during the fall session of the Parliament.

According to his previous announcements, compulsory military service will apply to men between the ages of 18 and 30. He also said that those who refuse to serve with weapons for reasons of conscience will be included in the system of the Ministry of Defense and the Serbian Army, where suitable places will be found for them to perform military service without weapons.

This has worried the Albanian community in the Presevo Valley, in southern Serbia, as memories of the 1980s - when ethnic divisions deepened in Yugoslavia and Belgrade's pressure on Albanians increased - are still vivid.

Valoni - whose real identity is known to Radio Free Europe - turns 18 this year. He says that compulsory military service has already become a topic of discussion among many young people in the Presevo Valley.

Aware of the possible legal sanctions, Valoni says he would not respond to the invitation to military service. And in that case, according to him, the only solution would be "leaving home and the country". The only Albanian MP from the Presevo Valley in the Serbian Parliament, Shaip Kamberi, submitted a proposal last month for the creation of a special commission, "with a mandate to clarify the cases of deaths of 135 Albanian soldiers in the ranks of the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA), during the 1980s". Kamberi said he obtained the data on these 135 soldiers - their names, surnames, periods of service and places where they served - from associations in Kosovo, which they collected from family members and the media.

"Another issue is when the Speaker of the Parliament, Ana Brnabić, will put this proposal on the agenda for a vote", Kamberi tells Radio Free Europe.

He adds that, considering that the majority of votes in the Assembly belong to Vučić's Serbian Progressive Party, he is not very optimistic that the proposal will be approved.

Natasha Kandic, from the Humanitarian Law Center in Belgrade, confirms to Radio Free Europe that, as part of the organization's research into human losses during the 1999 war in Kosovo, data has also been collected on the suffering of Albanians who served as regular soldiers in the JNA barracks. She emphasizes that this data is not complete, but contains the names and surnames of the soldiers, while their sources are families or the media.

"The data shows strange circumstances, that there have been suspected suicides in barracks in Serbia," says Kandic.

In three cases, according to her, the families received reports of suicide, but they doubt the veracity of these reports. The Speaker of the Serbian Parliament, Ana Brnabić, did not respond to Radio Free Europe's questions regarding MP Kamberi's request.

Neither did the Serbian Ministry of Defense provide a response to clarify whether it and the Serbian Army have information about the suffering of Albanian soldiers in the JNA barracks and the circumstances of their deaths.

The "perverted death" of a young man: The tragedy of Yzeir Sadiku

The death of Yzeir Sadiku, 25, during military service left an indelible wound in the family, his uncle, Sadik Sadiku, recounts.

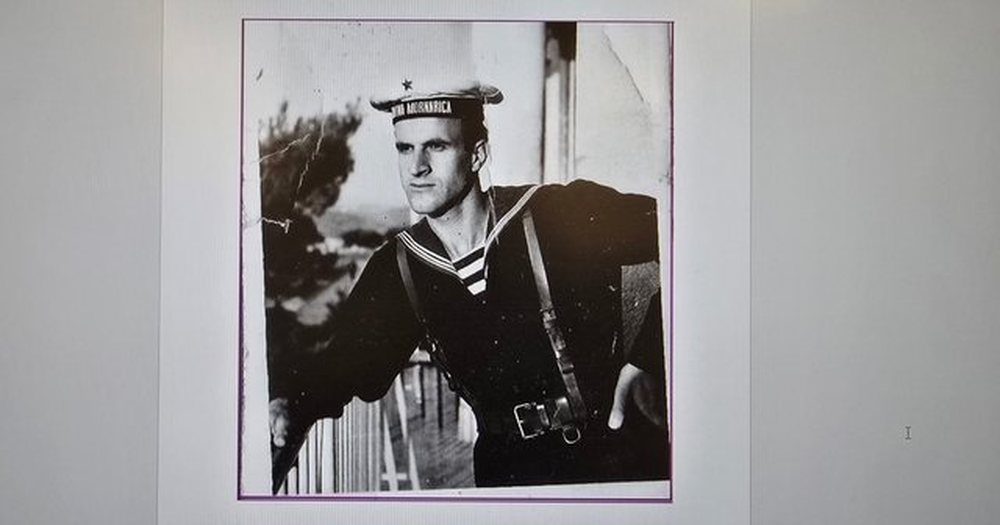

He says that Yzeiri had begun his military service in October 1981, after participating in the protests of Albanian youth in Pristina during March and April of that year, to oppose the political and legal position of Kosovo in Yugoslavia. Sadiku says that for this activity, Yzeiri was called to briefings by military superiors on April 11 and 12, 1982, at the “Lora” barracks in Split, Croatia, where he was serving as a sailor.

The next day, Yzeir's brother, Adem Sadiku, traveled to Split, after the family received a telegram from the JNA informing them that Yzeir was seriously ill. A little later, the family was informed that Yzeir had died. According to the official version of the military authorities, the cause of death was suicide - he had jumped from the building where the briefing was taking place. Sadiku recalls that Yzeir's now deceased father, Rrustemi, who was a religious imam by profession, also went to Split.

He managed to see his son's body before the coffin was sealed. According to Sadik, he saw signs of violence and torture on Yzeir's body - which led the family to suspect that he did not commit suicide, but was killed by his superiors who were interrogating him.

The decline of Albanian youth in the JNA

Yzeiri was not the only young Albanian who returned dead from compulsory military service in the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA).

"There's almost no day that I don't cry. What can I do... there's nothing a person can do," Mihanja tells Radio Free Europe.

The JNA military authorities brought her son's body to the entrance to the village of Bardh i Vogël in Fushë Kosovë, where the Krasniqi family still lives today. The family did not follow their order not to open the hermetically sealed coffin.

Mihanja wanted to say goodbye to her son before he was buried, in front of thousands of citizens. Abedin, then 21, had begun his military service in the Yugoslav People's Army in Manastir, in present-day North Macedonia. In September 1991, he was transferred to Knin, Croatia, on the front lines of the war that broke out after Croatia declared independence.

His family member, Fadil Krasniqi, says that Abedin was initially detained because he had refused orders from his superiors to join the war against Croatian forces.

Family members suspect that he was tortured while in custody. According to Fadil, Abedin was taken to an army health care facility in Knin on February 11, 1992, where he died. According to the official JNA report, he was accidentally killed by a Serbian soldier, but the family did not believe this version.

The family's suspicions were later confirmed by the symbolic punishment of the perpetrator of the murder. Since the early 1990s, Serbia's repressive measures were installed in those institutions and most Albanians were dismissed from their jobs.

KMDLNJ: These were not suicides, but executions

The Council for the Protection of Human Rights and Freedoms in Kosovo (KHDLNJ), established in 1989, has collected data on Albanian soldiers who lost their lives under suspicious circumstances while serving in the JNA.

The current director of the KMDLNJ, Behxhet Shala, tells Radio Free Europe that incidents involving Albanian soldiers increased after demonstrations in Kosovo in 1981, when Albanians demanded the advancement of Kosovo's legal and political position within the Yugoslav Federation. He explains that during the 1980s, verification of the manner of death by independent experts or families was almost impossible, as the bodies of young Albanians were returned to their families in hermetically sealed coffins.

Only close family members were allowed to attend funeral ceremonies, always under the watchful eye of military and security authorities. Although this practice was sometimes not fully respected during the 1980s, by the early 1990s, the situation had completely changed, according to Shala.

"At that time, Yugoslavia no longer cared whether families opened the coffins. In a way, the killing of Albanians became routine and was used as a political tool to achieve certain goals," says Shala, adding that the KMDLNJ, at the time, recommended that families open the coffins to see their relatives.

And this often revealed that it was not a suicide. Shala adds that about 70 percent of these murders occurred outside the territory of Serbia, in other republics of the former Yugoslavia, "so as not to arouse suspicion in public opinion."

Reasonable distrust

The situation is described similarly by the deputy of the Serbian Parliament, Shaip Kamberi. According to him, the relatives of a number of young Albanians who lost their lives while serving in the Yugoslav People's Army have opened their coffins and have concluded that the official version - death as a "suicide" or "fatal incident" - did not correspond to reality. Kandic also believes that the families of the soldiers, but also the deputy Kamberi, have the right to demand the investigation of these cases and the publication of existing documentation. According to her, the data should be found in the archives of the Serbian Army.

"If a survey commission were to be formed, it would have to be based on available data and then one would have to wait for state authorities to provide the data. So as it is now, this always remains an open question," says Kandic.

She adds that it would be useful if an institution in Kosovo would collect all the available data from various sources within the country. Speaking to Radio Free Europe, Kandic also mentions an event that, as she says, shocked the public in the former Yugoslavia, on September 3, 1987.

According to JNA authorities, at the barracks in Paraqin, Serbia, Kosovo Albanian soldier Aziz Kelmendi, from the village of Karaçicë, Shtime, allegedly shot dead four soldiers and wounded several others with an automatic weapon. Authorities reported that Kelmendi was found dead several hundred meters from the barracks.

Kandic says that after this event, the authorities seem to have deliberately tolerated the evasion of military service by Albanians, who fled abroad to avoid this obligation.

Kamberi now expresses fear that the return of compulsory military service, which the Serbian authorities are warning about, has precisely this purpose - the evasion of this obligation by Albanians of the Presevo Valley and their departure.

Therefore, he says, the issue of compulsory service does not only affect the past, but also the future of Albanians in the Presevo Valley. Albanian families are facing difficult choices, Sadiku also says. /REL./