In 1930s Tirana, as Albanian academic Lea Ypi writes in a forthcoming book, people debated whether corruption was “the cause of Albanian misery or its most natural consequence.” The same dilemma can still be heard in the Albanian capital. But one thing has changed: for the first time in the century-old history of the Albanian state, an independent anti-corruption unit is arresting politicians, officials and drug traffickers – unfazed by influence or high office.

The Special Structure Against Corruption and Organized Crime (SPAK) began its work in 2019. According to polls, 76% of Albanians trust SPAK, making it the most trusted institution in the country. More and more members of the Albanian elite, including senior officials of the ruling Socialist Party, have been caught in its web. Prime Minister Edi Rama is no longer as enthusiastic as when SPAK only arrested his opponents.

In 2023, SPAK placed Sali Berisha, former president and current leader of the main opposition, under house arrest. He is on trial for corruption. Ilir Meta, another former president and opposition leader, was also arrested, accused of the same offense. Former ministers in Rama’s governments have also been detained, and in February, it was Erion Veliaj, the socialist mayor of Tirana, considered a potential successor to Rama, who denied the charges. All deny the charges.

In the fight against organized crime, SPAK has had great success in cooperation with foreign police. An Albanian drug lord usually operates from Dubai. His buyers in Ecuador send the drugs to Europe, where his people take care of distribution. The profits are invested in construction in Albania, and his soldiers buy apartments. In July, SPAK seized assets suspected of being proceeds from drug money laundering from Switzerland, and accused another group of trying to smuggle weapons into Britain.

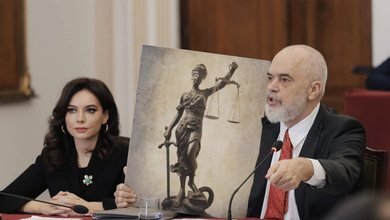

The arrests of politicians have sparked more debate. Berisha says Rama is persecuting him and calls SPAK his “whip.” But the growing number of Rama’s close associates accused of corruption has also damaged the prime minister’s image. When Veliaj was arrested, Rama accused SPAK of human rights violations. That drew criticism from the European Union; an EU diplomat called Rama’s accusation “nonsense.” Rama later backed down from the criticism.

Rama has promised that Albania will join the EU by 2030. A track record in the fight against corruption is a prerequisite, and some member states value SPAK’s cooperation in the fight against drug gangs. As much as Rama would like to defend Veliaj, he has come to understand that attacks on SPAK are politically damaging. A source in the judiciary cynically says: “If the political class were satisfied with SPAK’s work, we would have a problem.”

Erion Veliaj began his career as an anti-corruption activist. Since 2015, as mayor of Tirana, he has helped transform it from a rundown city into an attractive metropolis. But SPAK says he and his wife laundered money from developers through a scheme that also included donations to NGOs. Six months after his arrest, Veliaj remains in pretrial detention and has been formally charged since July 23. This is common in Albania, where 62% of prisoners are in pretrial detention – far more than in the rest of Europe. He has also been charged with witness tampering. On July 15, SPAK also charged another former Socialist MP with providing police information to a criminal during the election campaign. Veliaj, his wife and the two MPs deny all charges.

Arbi Veliaj, the mayor's brother, says that SPAK has "gone out of control" and is holding him in prison on unfounded charges. His arrest has divided public opinion in Tirana. Some compare SPAK to the infamous Sigurimi of the dictatorship. Others rejoice in the overthrow of the powerful, who they say have been stealing for years. The source from the judiciary emphasizes that the establishment of SPAK had one goal: to put an end to the "culture of impunity" in Albania. And if it succeeds, this would be the event of the century.