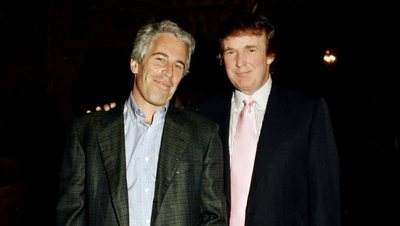

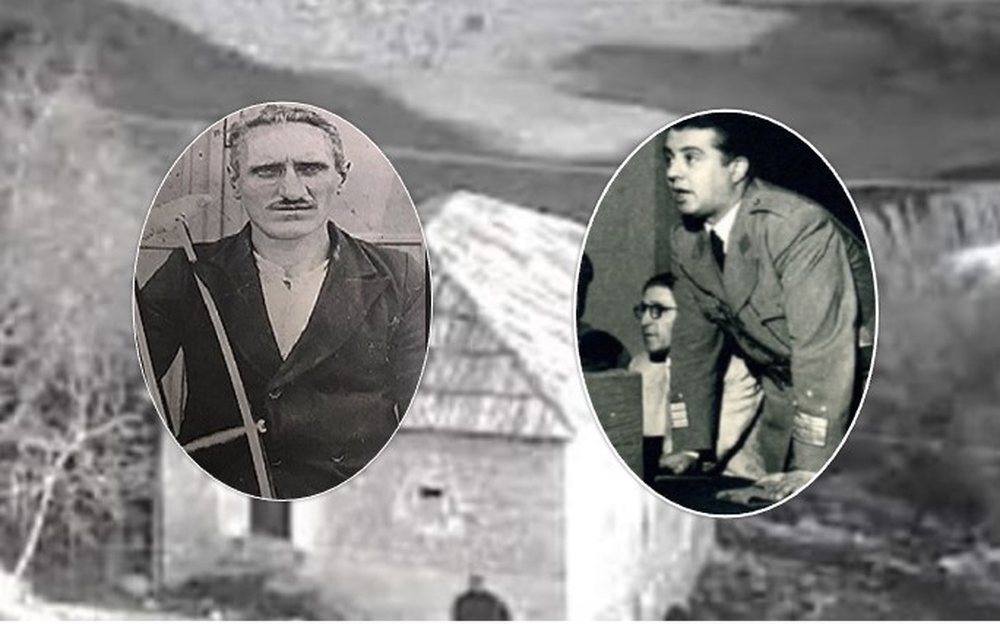

My father's story is the story of a man who never agreed with communism and who faced class struggle, differentiation and the consequences of absurd collectivization and total nationalization of the economy until his last breath. Mehmet Bubrrec Buçpapaj was born in 1914 in the village of Tplâ in Tropoja, into a family that, two generations earlier, had descended from the "Kapuçprush" neighborhood of Bujani i Epër. He was proud of his origin from Bujani i Krasniqa and to show this affiliation, he always signed himself 'M. Bujaku'.

From a young age he showed a thirst for knowledge. Although self-taught, he managed to be one of the most knowledgeable people in the province. At the age of eight, he went down to Shkodra with his father to register as a boarding school student. He successfully passed the exams and was registered in the third grade. He fell ill with the flu and his father was forced to take him with him. His dream of continuing his studies in school did not come true, but he never gave up on knowledge.

My father taught reading and writing to his younger brothers: Ali, Xhemajli and Halil, the son of aunt Sejdi Braha (Doçi), cousin Ali Ibishi (Buçpapaj) and fellow villager Qazim Zeqa (Malaj) and nephew from Iballa, Ibrahim Dauti. Xhemajli, Sejdiu, Ali Ibishi, Ibrahim Dauti (from Iballa) and Qazim Zeqa, became among the main high-ranking cadres in Tropoja and always preserved the calligraphy of their first teacher.

He was only thirteen years old when his grandfather, Bubrrec Alia, was imprisoned. He, along with another mountaineer, had taken on the task of collecting taxes for all of Tropoja. They failed to collect the taxes regularly, the partner denounced him as his fault, and the grandfather was imprisoned.

The father went to the sub-prefecture center in Tropoja to learn about the fate of Bubrrec Alia. He was told that he had been sent to the Kukës prison. Zenun Col, a lawyer and employee of the sub-prefecture, felt sorry for him and decided to help him. He gave him a letter to the best lawyer in Kukës, with whom they had finished their studies. He advised him to follow the telephone poles, so that he could go straight to the city of Kukës. The lawyer immediately agreed to take on the case. The father was happy when he convinced his grandfather to cooperate as closely as possible with the lawyer. The accuser's accusation was dropped and thus Bubrrec Alia was acquitted.

Grandfather was a patriot. In the battle of Qafë Morina in 1909, he was wounded in the leg, but survived. In this battle, his cousin, Ali Jakup Buçpapaj (Papuça), was killed in the muzzle of a Turkish cannon. Even today, his song is sung in Malsi and Kosovo. A few years earlier, in April 1881, Smajl Hysen Buçpapaj had been torn to pieces by Turkish cannonballs, along with his fellow villager Mic Sokoli. This moment has also been immortalized in folk song.

My grandfather had been a student at the Skopje Madrasah, where he had learned Ottoman, but he had to stop because his father died prematurely and, as the only son of the family, he had to deal with the family, the properties, the inherited wealth. My grandfather was a learned man. He knew Ottoman from the Skopje Madrasah, which he had also taught to my father, Mehmet, who had a penchant for everything. From a very young age, my father stood out for his talent as a master builder, but also as a simple designer.

He became sought after in the construction of new towers throughout the Highlands. At this time, he formed close and permanent friendships with such masters as Hasan Uka of Luzha, Shaban Syla of Babina, Ali Haxhia of Luzha, Zeqir Halili of Viçidol and others. Even before joining the army, he took on and successfully completed the construction of the tomb of Sheh Ali in Tplâ. He finished his military service in Shkodra in 1934. He was a soldier who stood out for his physical, but also theoretical preparation, and this is confirmed by the decorations and awards he had received from the Ministry of Defense of the Kingdom, (or as it was called at the time; the National Army).

At that time there were few young men in the country who could read and write, and even fewer with the quality of our father, who excelled in the acquisition of military doctrine. Father was also a prominent marksman, a sniper as they say today, even the best of his time, in the Royal Army. His superiors wanted to keep him in the army, offering him to pursue the necessary qualifications to become an officer, but father refused them, due to the need to return home, to his family, but he would never sever his ties with Shkodra.

There he met talented merchants of that time. Father, being a man of culture, even one of the most cultured in the Gjakova Highlands at the time, during the period of the army in Shkodra, but also during the years of trade with this city, had bought almost all the publications that dozens of Shkodra printing houses were publishing, creating an astonishing library with books by well-known authors, including those of Gjergj Fishta. In Shkodra he had also learned Italian, in order to read and communicate sufficiently. Based on these, he became a man of determination for the market economy and trade, and Shkodra gave him this opportunity.

Baba most often mentioned Man Tepelina, one of the most prominent merchants of Shkodra at that time. He established connections with these merchants and, as soon as he finished his mandatory military service, with his fellow villagers, Rexhep Selimi (Mehmetaj) and Bekë Sylejmani (Ponari), they opened a private shop in the village. They were the same age as Bekë and had maintained a close friendship throughout their lives. Their trade was successful. One of them, in turn, stayed in the shop. The other two sent goods by horse caravans to Shkodra and received goods from there. Their clients were from different villages, from both sides of the Drin.

According to tradition, since the League of Prizren and onwards, our family was among the first in the Highlands to join the formations of the fight for freedom. Our house became a shelter for fighters, such as Fadil Hoxha, commander of the General Staff of the Kosovo National Liberation Army, Emin Duraku, Hajdar Dushi, Xheladin Hana and others. In Fadil Hoxha's memoirs; "When Spring is Late", there is a character named Bubrrec, but Fadil set the events in another village in Tropoja, avoiding the risk that his character would suffer from the regime of Enver Hoxha.

My father had no respect for Fadil. He had met him in Tirana, when, for some reason, he had gone to meet Kolë Bibë Mirakaj, then Minister of the Interior. Kolë was from Iballa e Puka, a neighbor of our grandmother's people, who were also from Iballa. My father said that Fadil would chant "Duçe-Jakomoni" until his voice was exhausted. I thought that my father was simply angry with Fadil because he spoke against the student demonstrations of the spring of 1981, which is why he gave him excessively negative connotations. But much later I read that Fadil had been an activist of the Fascist Party.

But he showed respect for Hajdar Dushi, who had and read communist literature in the original German. It is said that he also drafted the Resolution of the Bujan Conference, which sanctioned that Kosovo would self-determine after the end of the War, "to unite with Albania". He showed without demagogy that the communists would not allow private property, would collectivize agriculture, would ban religion, and would wage class warfare against any disagreement with communist ideology.

Our family had a tradition of fighting against invaders, where since the League of Prizren, in the Plavë-Gucia wars and until today, 23 sons of the Buçpapaj tribe have fallen fighting on the land of Kosovo and have been declared martyrs. So the opening of the chrome mine in Kam, by the Italian invaders, was considered by the highlanders as a theft of our national wealth, who organized an armed attack in which our uncle Fazliu also participated, along with our cousins, Selim Braha and Halil Beli, etc.

The fascist regime pursued them and the uncle went to the mountains, while the family joined the anti-fascist resistance. The Italian fascists, on the eve of the winter of 1942-'43, in revenge, decided to burn our tower, as a participant in the anti-fascist resistance and as a shelter for freedom fighters. They burned the cattle stable, while filling the entire barn of the Buçpapaj family's large house with hay and corn straw, to set it on fire as well.

But Xhemajl Bubrreci, only 16 years old, together with Isa Selim Bajraktari (the aunt's son), opened fire on them. The Italians were forced to respond and pursued them both to Molle i Kuqe (Bujan), but to no avail. The large house escaped arson, while the family was not safe, so they moved to Iballe i Puka, to their father's uncles, until spring. With the formation of the first National Liberation Councils, the father elected secretary for Tplâ-Dushaj, while Hoxhë Dusha was elected chairman.

My father married my mother, Gjylë Ismail Meshi, on January 1, 1944. The wedding, the escort of the bride from the village of Kosturr i Hasit, took place in the village of Shëngjergj, on the banks of the Drin. The friend of the house, Din Zenel Bajrakari, who was a delegate to the meeting of the Bujan Conference, was absent from the wedding, as was the son of my father's aunt, Selim Braha, who was a guard at Sali Mani's house, where the conference was being held. They came on the second day of the wedding.

In 1944, our family was denounced for possessing and distributing partisan tracts. The Nazis, after raiding the entire house and finding nothing, lined them up, young and old, in front of the people.

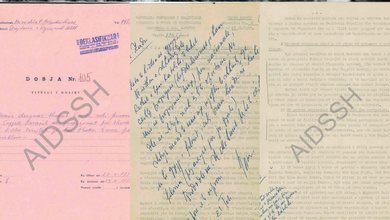

The village elder, Ahmet Alia (Ponari), guaranteed that the denunciation was false and saved our family from danger. In 1945, my father was elected chairman of the National Liberation Council for the village of Tplà-Dushaj. This is where the first clashes between my father and the communist government began. That year, Fazli Bubrreci, my father's older brother, one of the first freedom fighters in Tropoja, a squad commander in the 25th Assault Brigade, was imprisoned in Shkodra. He was accompanied by a file from Yugoslavia, all in Serbian. My father obtained certificates from all of his uncle's comrades-in-arms and as a result, he was declared innocent.

One of the first measures taken after the establishment of communist power was the delivery of all books by "reactionary" authors to the center of the district. So his father and brother had to carry the books on horses and deliver them, according to the order, which the communists burned. Most of these books, such as those by Fishta and Catholic writers from the north, but also many translations, had been declared prohibited by the communist regime. In the context of nationalizations, the father and his two partners were forced to close the private shop. The first state-owned shop was opened years later.

Meanwhile, my father, as a man of talent and courage, had opened the first wool processing workshop in Tropoja, with which he earned a lot. He did the basic processing in Tpla and then sent it to Shkodra, where he sold it at a higher price. He had also opened the first milk processing workshop (for extracting butter) in the province, where he again secured income from the customers themselves and from the farmers. He had plans to expand his business, but the communist regime came by narrowing private property, to the point of its disappearance.

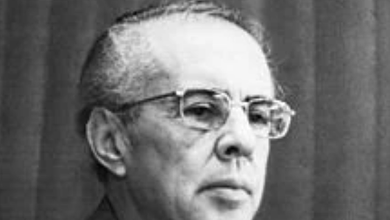

My father fell into deep disagreement with the regime when the authorities in the center of the district, after having declared his younger uncle, Halil Bubrreci, a courier for partisan formations, killed in the summer of 1944 in the mountains, a martyr, stripped him of this title with unfounded arguments. In those years, which are also called the “Koçi Xoxe period”, it happened that mountaineers were arrested in their homes and killed on the way to the center of the district, under the pretext of trying to escape. Even those who escaped the bullet were beaten until they were taken to the hospital.

The most frequent accusations against the mountaineers at that time were for “hiding weapons”, for “sheltering fugitives” against the regime, or for “sending food and clothing to the mountains”. In all cases, the father personally accompanied all the arrested people to the center of the district. He even went so far as to argue that they were completely innocent. The accusations, almost entirely, were baseless, simply made for old revenge.

In 1949, my father volunteered for the final phase of the Maliqi swamp's drying. There, he worked as a bricklayer in the canal, in cold waters, and returned home sick, in such a state that no one recognized or believed that it was really him, Mehmet Bubrreci. He was almost completely paralyzed in both legs. By chance, he escaped without having to amputate one leg.

He was in the operating room, arguing with the doctors, because he refused to have the operation under anesthesia, when the news came that the treatment had been approved and the medications ordered by UNRRA had arrived from the Civil Hospital in Tirana. The treatment would continue for a long time. Every year he spent at least a month in the hospital. Until recently, the crutches he used during that period were kept at home. Later, for several more years, he moved with a cane.

During this period of time, not having much hope for a full recovery, he bought a sewing machine and decided to take up tailoring. In our house, until recently, there was a sewing machine, which my father had only used for a few years. At this time, my great uncle, Fazliu, was imprisoned for the second time. This time he was accused of agitation and propaganda. In 1948, after the break with the Yugoslavs and the closure of the border with Kosovo, it became clear that it had remained with Serbia.

Great Uncle Fasllia publicly accused Enver Hoxha of betraying Kosovo and the liberation war itself, since he and his three brothers, like most of the mountaineers of Tropoja, had joined the ranks of the XXV Assault Brigade, to liberate Kosovo from the Nazis and unite it with Albania. This concept was also expressed in the resolution of the Bujan Conference, but now, along with Kosovo, Serbia also had Gjakova, a vital city for the Gjakova Highlands. Until his death, when his uncle was bored, he sang the famous song in the Highlands; “Hajmedet se u mshel Gjakova”!

For this, the uncle was sentenced to 15 years in political prison. He was targeted by the head of the Branch, Kopi Niko, one of the greatest executioners of the communist dictatorship. The father met again with all of the uncle's comrades-in-arms and took their statements. He also met with the witnesses and they changed their testimonies. The uncle was finally sentenced to only one year in prison. But he stayed in prison for two years, since the Supreme Court's decision had remained in the prison secretariat's files and only a check from above revealed the letter for the uncle's release.

My great uncle, Fazli Bubrreci, was treated completely unjustly by the communist authorities in the village and in the district until the end of his life, as a political convict, with 15 years in prison. In all our official biographies, my uncle appeared as a convict of 15 years in political prison. The official circles in Tropoja considered that our family, with its post-war stances, had denied the war it had fought.

Thus, in the history of the National Liberation War of Tropoja, which ended in the 1980s, the role of our family in the National Liberation War was reduced only to the name of our grandmother, Shkurtë Isufi, as the mother who had welcomed and escorted partisans. At a time when the two uncles, Ali Bubrreci and Xhemajl Bubrreci, received veteran's pensions, because, with documents, it was proven that they were voluntary participants in the National Liberation War.

This designation was given to all those who had participated in the formations before the Përmet Congress on May 24, 1944. After that date, all participants in these formations were no longer volunteers, but were mobilized recruits and participation in partisan formations was considered compulsory military service. In this last category, all participants in the XXV Assault Brigade, with fighters mainly from Tropoja and Has, entered.

This was an extreme injustice to our family, one of those flagrant deformations that have left Tropoja without a local history of its own. In 1953, an agricultural cooperative was established in Tpla, the first in Tropoja and one of the first in the north of the country. A year earlier, the four brothers – Fazliu, Mehmeti, Aliu, Xhemajli – had been separated. Because the land that belonged to their father was somewhat further away, he did not belong to the house, so he began building his own house. The other three brothers were among the first to join the cooperative.

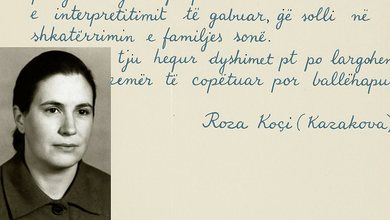

My mother, thanks to her physical health, her spiritual formation and the perfect education from the family she came from, from the Meshajs of Kostur, would be my father's strong right-hand man in all challenges. She faced with dignity the burden of the house and raising the children, but also the fall of her brother Isuf Meshi, in political prison, for 25 years. My father requested a disability pension. He had to write letters all the way to the head of the country. As soon as he filled out the pension documents, a fire broke out in the Executive Committee of the district and every document was burned, including my father's pension documents.

This, but also his formation for the free market economy, influenced the firm decision of his father not to become a member of the agricultural cooperative and this put our whole family at the center of the class struggle in the village, much more fiercely than against the kulaks, former kulaks, political prisoners or former political prisoners of the village. These entered the cooperative as soon as they were given the first chance. And they were the most obedient to the party line. From the 1960s, Tplani also became an internment center.

Even towards the internees, the leadership of Tplàn maintained a significantly softer attitude than towards our family. I was little when the chairman of the cooperative, together with the leadership, came to the yard of our house. My father came out, and so did I. The chairman asked my father to join the cooperative and reminded him that he was the only one who had not done so in our village. My father objected firmly: “I am a sick man, an invalid without a pension, I have many children. The cooperative cannot support us”! / Memorie.al/