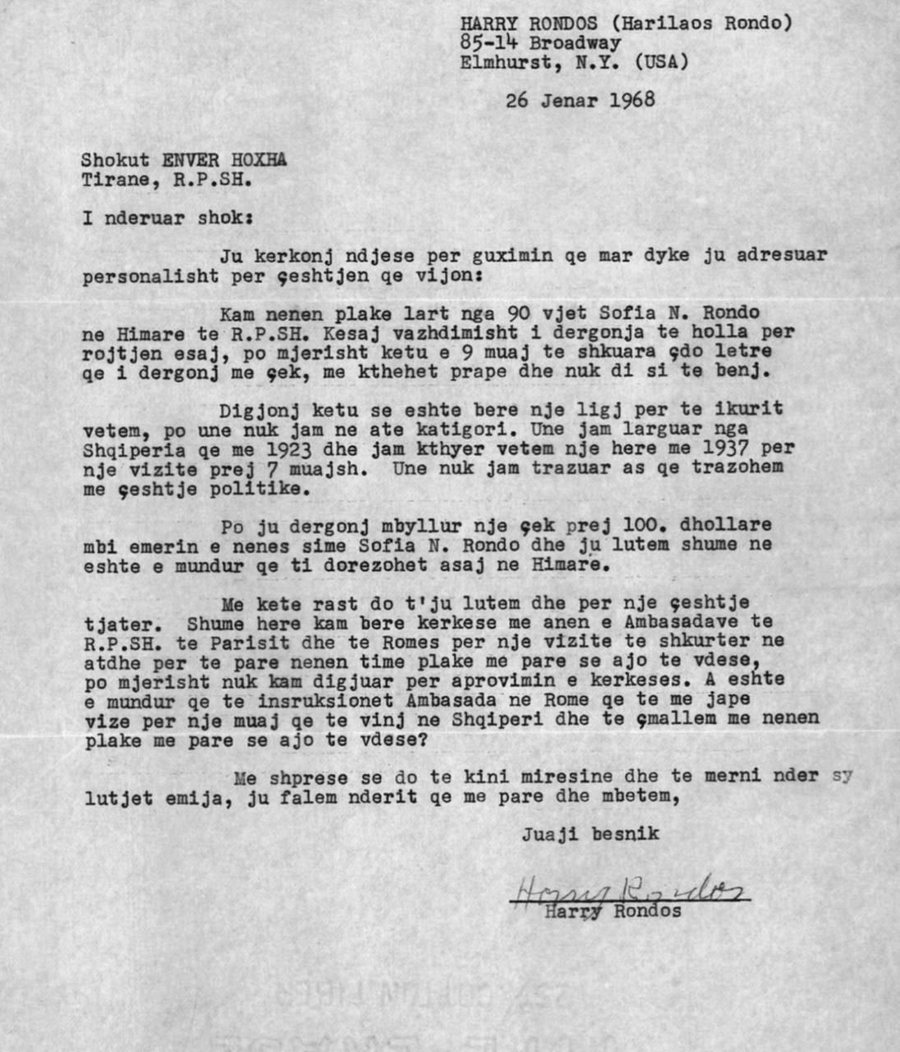

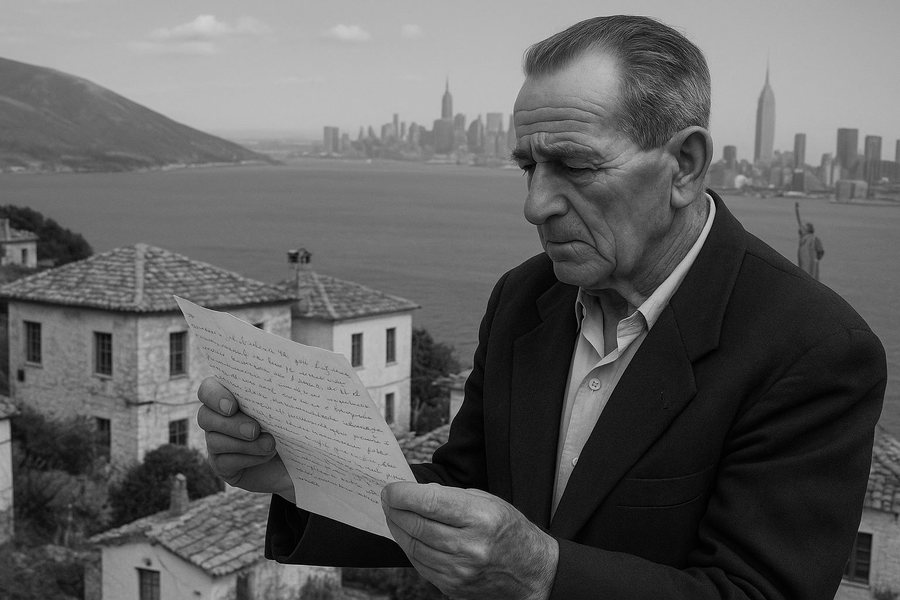

In the cold January of 1968, from a modest apartment in Elmhurst, New York, a 65-year-old man named Harry Rondos wrote a letter that would never be answered. The letter was addressed to Enver Hoxha himself, with the humble tone and simple hope of a son who wanted to help his mother at the end of her life.

“I have an old mother, over 90 years old,” Rondos wrote, “and every letter I send her by check comes back to me.”

In the envelope, along with the letter, he had included a check for $100 for Sofia — the woman who had been left alone in Himara, in an isolated and frightening Albania, where connections with the outside world were considered a sin.

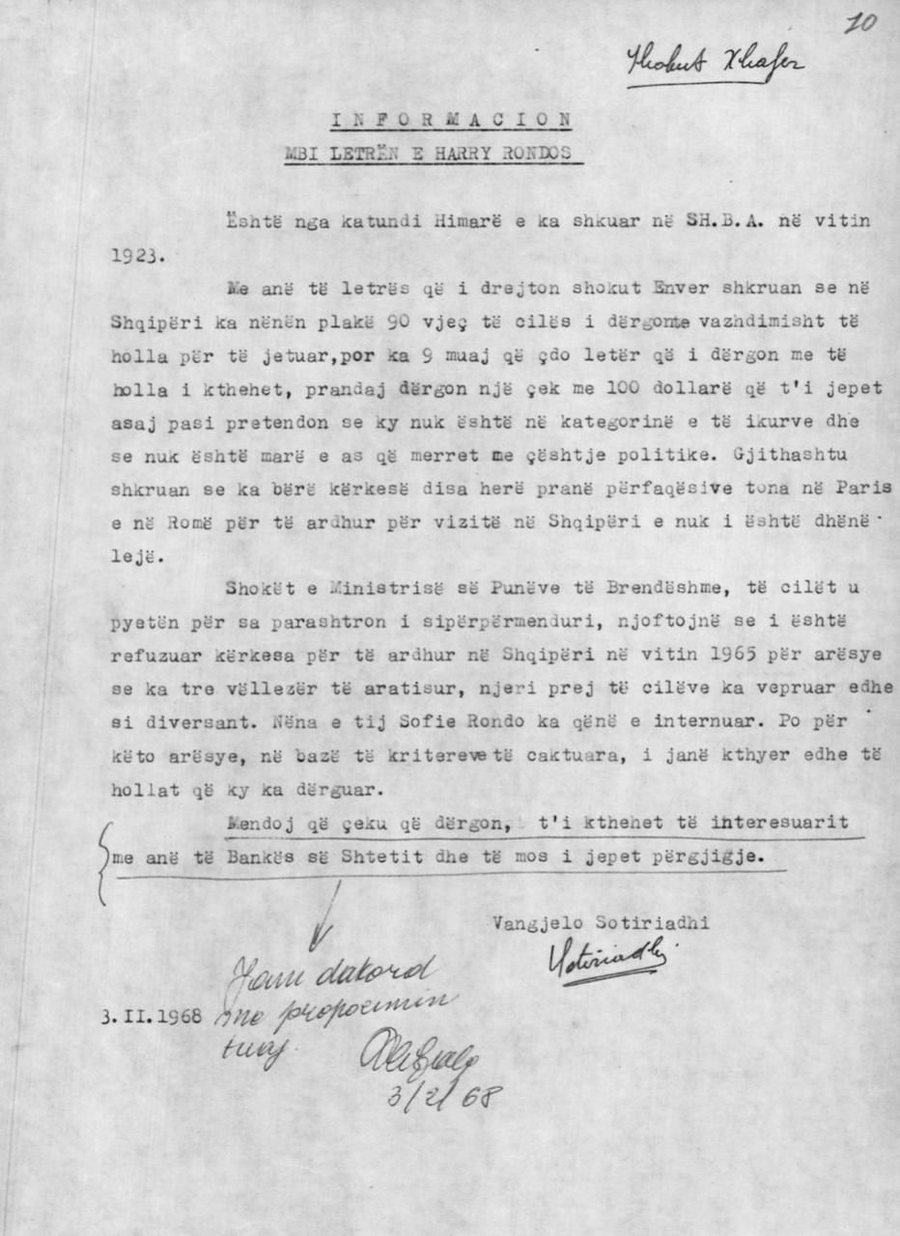

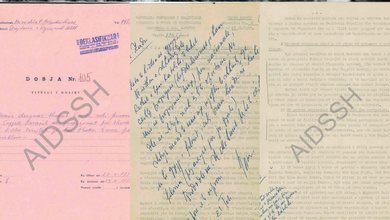

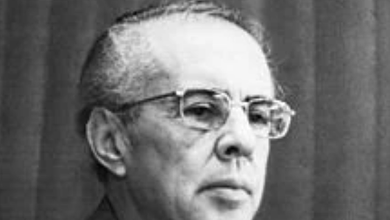

But the state saw neither the love of a son nor the mercy for a mother on the verge of death. In the official file, “comrades from the Ministry of Internal Affairs” defined his request as “unacceptable.” Harry Rondos could not enter Albania — he had three brothers who had escaped, and one of them was called a “saboteur.” For this reason, his mother was interned and every dollar sent to her was returned.

At the end of the bureaucratic document, a cold sentence seals the fate of his prayer:

"I think that whatever he sends should be returned to the interested party through the State Bank and no response should be given."

Today, that letter remains as a small, but poignant testament to that time when an exiled boy sought mercy from a system that knew neither love nor mercy.

And perhaps, somewhere in Himara, in a house that no longer exists, mother Sofia waited until the end for the postman to bring her news from America.

But the letter with the boy never arrived.