From 1 January 2024, Kosovo citizens will finally be able to travel to the Schengen area without a passport without going through bureaucratic procedures at foreign embassies. They are the last in the Balkans to gain this right, preceded by Albanians who gained it in 2010. Analysis of illegal Albanian border crossings during and after the communist era shows that the visa waiver was the result of a long-term struggle against one-sided systems of surveillance and profiling that still affect people’s lives.

Turning the border into a "death zone"

Illegal border crossings in Albania began after World War I, when the borders separating the country from the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes – later Yugoslavia – and Greece were fixed by the Great Powers. Those who remained on the Albanian side were cut off from traditional circles of mobility and exposed to hunger and violence. Illegal border crossings became a necessity.

After the end of World War II, the breakdown of Albanian-Yugoslav relations in 1948 and the civil war in Greece turned the borderlands into one of the most dangerous places in the Balkans. The borders and borderlands were strictly controlled by the Albanian army, initially as a means of preventing attacks from abroad. From 1945 onwards (1991), they served mainly to prevent the escape of Albanians.

The communist government created the Border Force in 1945. An area known as the border belt was established along the border to prevent the free movement of non-locals. The soldiers moved on foot, motorbikes and boats, depending on the terrain. Their work was facilitated by tools and technologies such as the soft belt – a strip of earth that protected the tracks – and the “electric signal barrier”, also known as the clone.

The clone was a fence placed hundreds of meters in front of the border. It emitted a signal when someone touched or cut its wires. The space between the clone and the border was a death zone. Even if violators evaded the guards, they would eventually be caught by border dogs. The most effective tool to stop illegal immigration was the bullet of the AK 56 assault rifle, the standard weapon of border soldiers.

The authorities believed that border protection began at home. The government passed harsh laws to deter people from trying to escape. According to the Penal Code, any illegal crossing from inside to outside was an act of treason. The penalty ranged from ten years in prison to death. Violators were called “enemies,” “agents,” “traitors,” or “bandits.”

The local population was mobilized to help the authorities. They were asked to report suspicious persons and form “volunteer forces” to pursue those attempting to cross the borders. The Ministry of the Interior monitored people with “liberal” leanings and “bad biographies” who were thought to be likely to escape.

The defense of the border was fueled by the cult of the border, a core nationalist myth of the communist era. The borders were sanctified by the blood of soldiers who died fighting foreign armies and political dissidents. Several monuments commemorating their sacrifice were built in the border areas, and the columns marking the state’s borders became a central element of the border mystique. They were called “pyramids.”

The border became a popular theme in art and culture. In November 1961, an art exhibition was inaugurated in Tirana to celebrate the heroism of the border guards, who were compared to national figures on the scale of Skanderbeg. Ironically, the author of some of the works, Zoi Shyti, himself crossed the border illegally a few years later.

“The art of illegal border crossing”

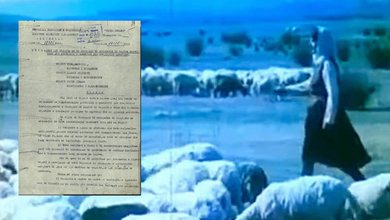

The strict measures taken to guard the borders did not prevent people from attempting to cross them. “The art of border surveillance” (Jorgo Qirici, Ruajtja dhe protsertja e kufirit shqiptarë, 2017) was opposed by the art of border crossing. In September 1956, 56 people from the village of Gërmenj in Ersekë (Kolonjë district), crossed into Greece and took with them a herd of 900 cattle and 40 animals loaded with materials.

Attempts to flee the country increased in the late 1960s, especially among the younger generation. People studied the terrain, sought the support of the local population, and attempted to cross the border using various means, such as ladders. Some people used cars to speed past checkpoints; others hid inside trucks and boats.

According to Jorgo Qiric, between 1966 and 1975, 526 people attempted to cross the border. Only 166 were caught. One of those who escaped was Demir, whom I spoke with in Tirana. Born and raised in the capital, his family came from Stebleva, a village on the border with North Macedonia.

When he finished high school, Demir was denied the right to go to university to study architecture because his family was known by the communist regime as former supporters of King Zog, and the party gave priority in higher education to students from working-class families with "clean" biographies.

Instead, the state sent Demir to work at a power plant in Vau i Dejës. His frustration convinced him to go to Yugoslavia and find his aunt, who lived in Skopje. “I thought about leaving all day and all night,” he told me. A relative’s wedding gave Demir the opportunity to go to Steblevo and get closer to the border. Escape ideas and plans often stemmed from conversations with friends. People talked about politics, anti-conformist music, movies, and other “subversive” topics.

The fear of being spied on was great, but, according to Demir, people would have gone crazy if they kept everything to themselves. He confessed his intentions to a friend who gave Demir the names of his relatives in the town of Dibra, just across the border. Demir went to Steblevo at the end of September. On the 27th he left the wedding and followed his cousin who was herding sheep near the border. Demir was able to spot the “gentle breed”.

It was a rainy day. The sheep had gathered because it was cool. Demir waited for the right moment and crossed the border. After spending the night near the border, Demir ate some apples and started walking towards Dibra, 25 kilometers away. He found the house of his friend’s relatives and told them he wanted to go to Skopje. They offered him shelter for the night. Demir slept until the afternoon, unaware that those he trusted were actually “opening his grave.” The next day they took him to the Yugoslav police.

Demir explained that he was a political prisoner and had come to Yugoslavia to stay with his aunt and study. He was sent to a “re-education” camp in Idrizovo, near Skopje, where he stayed for four months and was not allowed to contact his aunt. One day, the police told him that his request to study had been accepted and that they would bring him to Belgrade. This was a terrible lie. Instead, they sent him to the Qaf Thana border post. “That was the end of my life,” Demir told me bitterly.

Albanian border guards brutally beat him. The torture continued in Tirana prison, where sadistic interrogator Isa Halilaj beat him with a metal baton. When he was brought to court, he was so weak that even his mother could not recognize him. The court sentenced him to ten years in prison. He spent four years in a prison camp in southern Albania and six years in the notorious Spaç prison, where he worked in the mines.

But prison sentences and death sentences did not stop Albanians from planning their escape. Archival documents show that many people convicted of crossing the border tried again when they had the chance. In the late 1980s, the regime began to crumble. The economy was in decline. A 1981 report says that most of the people who had attempted to escape were from the “poor” classes, indicating the structural failure of the socialist state.

Albanians lose patience as communism collapses in Europe

Petroja was in his early twenties when he decided to flee. He could no longer bear to live in a country that offered him few opportunities to fulfill his dreams and where party sympathizers told him how to cut his hair. Many people of his generation felt that they were wasting their lives in Albania.

The pressure to leave was summed up in the phrase: "O men, let us free ourselves!"

Petroja went to the borderlands in October 1988, when a friend invited him to a wedding in Zagrad, in the Dibra region. Intoxicated by drums and plum brandy, Petroja surveyed the mountains that separated Albania from Yugoslavia. The border was very close; why not go to the other side? Petroja asked someone from the village to take him to the border. The man agreed, but asked what he would do on the other side.

“I don’t know,” Petroja told him. “Maybe the Serbs will arrest me. But I can’t stay here anymore. I just want to leave!” Petroja returned to Zagrad in February 1989, determined to escape. He had taken a small pig with him as a gift for his friends in the village. But just a day before his escape, the terrifying sound of machine gun fire filled the space between the mountains. Two people were killed and one was wounded. The controls were temporarily tightened and Petroja had to return.

As communist Europe was ending, so was the patience of young Albanians, who were more willing to risk their lives on the borders. Petroja tried to escape several more times. In 1990, he heard that there was a crack in the border with Greece near Korça. He went there, but found a terrible situation: “People were being killed every day. Border dogs were eating people.”

He wisely decided not to take any chances. The days of the communist regime were almost over, but the army was still using all its might to prevent people from crossing the borders. In March 1990, the commander of the border forces ordered soldiers to continue using machine guns and grenades to stop people trying to cross the border.

The communist regime fell in December 1990 and illegally crossing the border was no longer considered treason. This change encouraged more people to take their chances and leave. In January 1991, Petroja received a tip. The border could be crossed near Gjirokastra. He went there with two friends, and the group continued to grow as they met more people on the way to the border. Two people offered to take them to the border, and Petroja's friend gave them his watch for it.

Thus began the “business” of illegal immigration to Albania. When they reached the village of Jorgucat, the group numbered about 100 people, including many women and children. Some went ahead to check if it was safe to continue their journey. The border was guarded, but the clone had been damaged. This part of the border had two clones. Immediately after they crossed the first one, bullets were fired over their heads. The group lay on the ground. Two soldiers and an officer approached them.

The officer gritted his teeth and threatened to kill them, but then demanded money. The group had no money, so they gave them their rings and watches and the officer let them pass. After 36 hours of walking, the remaining members of the group entered Greek territory and reached the paved road. Petros was impressed by his first contact with a world that seemed more civilized than the one he had left behind.

The group was stopped by Greek soldiers. After the Albanian soldiers had taken their belongings, the Greeks took their identity. All their documents were confiscated. They asked them their names. Those with Christian names were sent to the Amyntaio camp; those with Muslim names went to the Kozani camp. The Greek authorities treated the Christian Albanians well, but behaved very badly towards the Muslims.

Petroja has fond memories of the Greek people who helped him, but the violence of the Greek police against Albanians who had committed crimes was no different from the violence of Albanian border guards against those who tried to escape. Petroja also criticizes the Greek government for not returning his passport and providing him with documents. For years, he was forced to cross the border illegally, to visit his family in Albania and then return to Greece where he worked. In the early 1990s, illegal border crossings became routine for him and many other Albanians.

Borders are not just about territory

After December 1990, the experience of crossing the border took on different meanings for Albanians. The rhetoric of the border between “socialism” and “capitalism” had just ended. But Albanians began to deal with more primitive and ubiquitous concepts of borders, for which there were no clear territorial boundaries. The border was almost everywhere they could be heard or seen.

It was in their clothes, in their “loud” appearance, in their accent, in their ethics and customs, in their tired and prematurely aged faces, in their poverty, in their language, in the shame of their failed state and politicians, in their innermost being of unwanted people. The communist dictatorship judged people by their biographies.

Capitalist states took a more radical approach: people were not judged simply by their deeds or their families, but by the characteristics of nations, races, and religious groups. The doors of the world finally opened to the Albanians because they had knocked them down at the cost of their lives. But, as the past precedes the future, guards with dogs and guns will continue to follow them wherever they go./ Memorie.al/