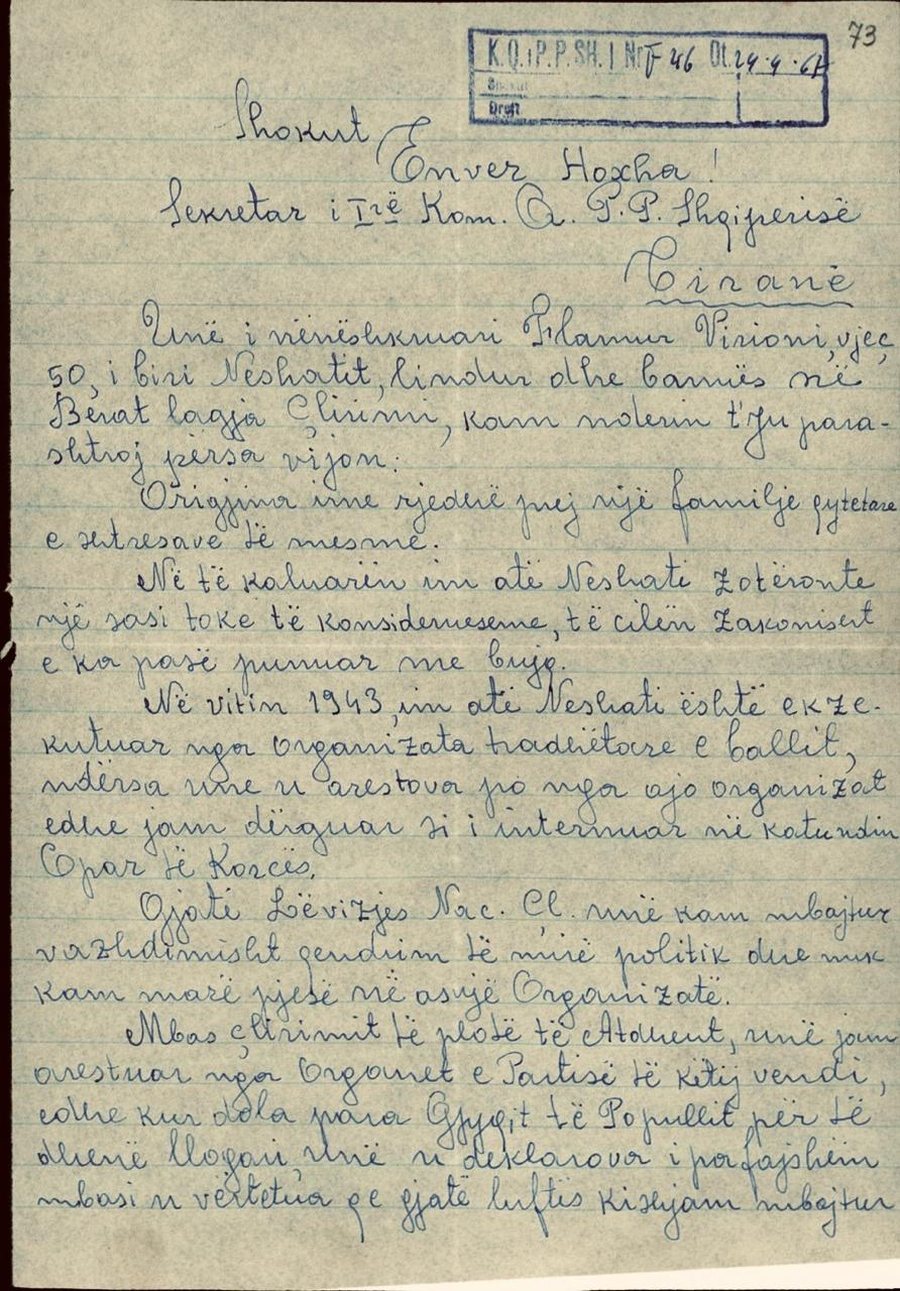

On April 24, 1967, Flamur Vrioni from Berat sat down and wrote a letter to Enver Hoxha. He was 50 years old, a resident of the “Çlirimi” neighborhood, and was faced with a life-changing decision: moving from his hometown to a village where he would have to work in an agricultural cooperative.

In his letter, Flamur tells the story of his family and the reasons why he wanted to stay in Berat. He explains that he came from a middle-class bourgeois family. His father, Neshat, had owned land, but this wealth was not inherited by him. On the contrary, in 1943, Neshat was executed by the National Front, while Flamur himself was exiled to Opar in Korça.

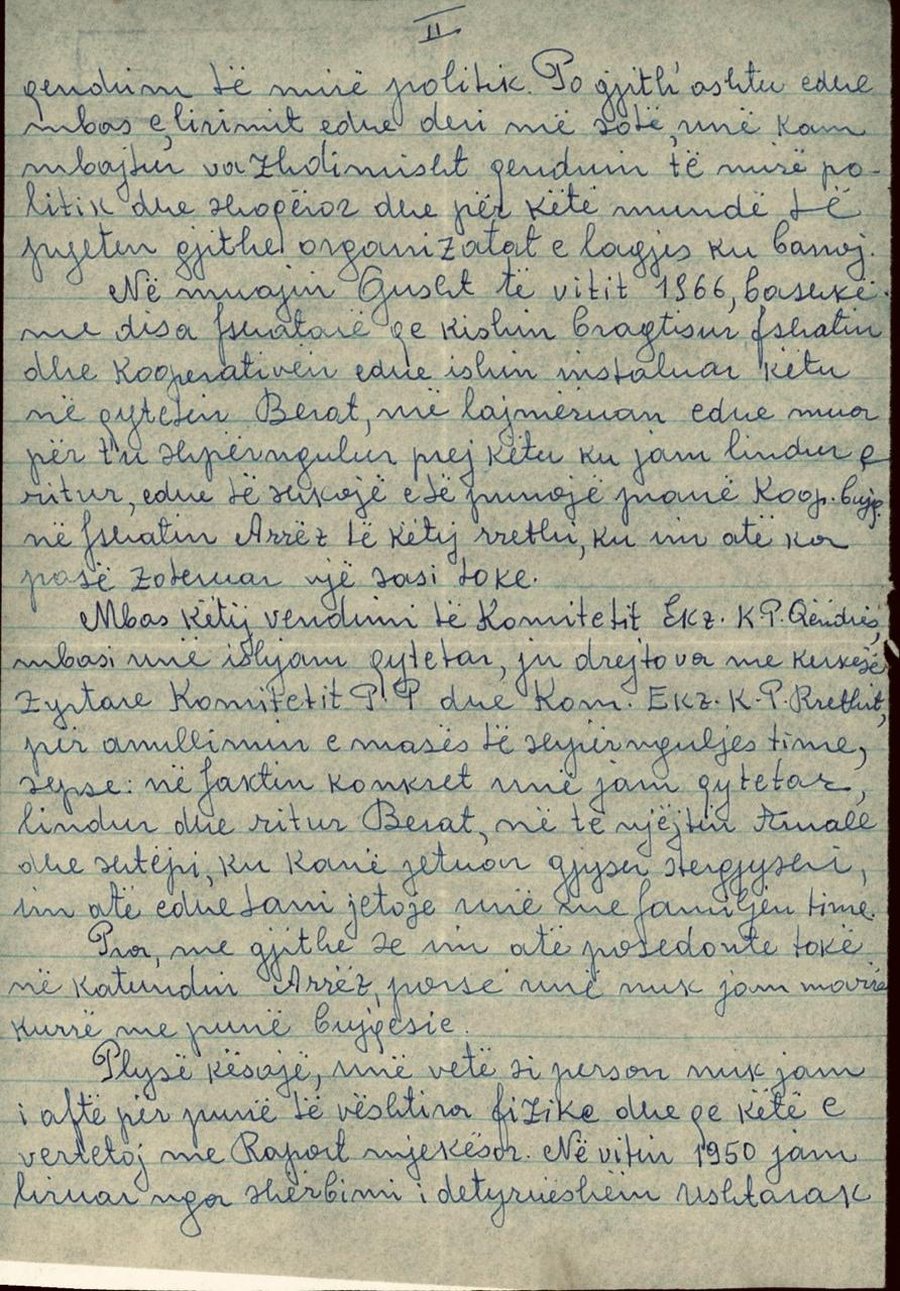

During the National Liberation War, as he writes, he had maintained a “good political stance” and was not involved in any organization. However, after the liberation he was also arrested by the organs of the new government, but was declared innocent. For years afterwards, he insisted that he had continued to live as a proper citizen, which any neighborhood organization could attest to.

In August 1966, when some villagers had abandoned the cooperatives and settled in Berat, he was also told that he had to leave. The decision sent him to the village of Arrëz, where his father had once owned land. But Flamur wrote to Hoxha that he had never been involved in agriculture, that he did not know such work and, above all, that he was incapable of heavy physical work. He brought as proof of this a medical report and the fact that in 1950 he had been released from compulsory military service.

His letter is a long and humble narrative, where every sentence attempts to defend his right to live on the land where his grandparents and great-grandparents had lived. He presents himself not as an opponent, but as a devout citizen who seeks understanding: not to be torn away from the neighborhood and the house where he was born and raised his family.

This personal appeal by Flamur Vrion is a vivid slice of the reality of that time, where people often turned to the supreme leader himself to escape from decisions that determined their fate. And between the lines of his letter, a simple call is clearly heard:

"Don't throw me out of Berat."