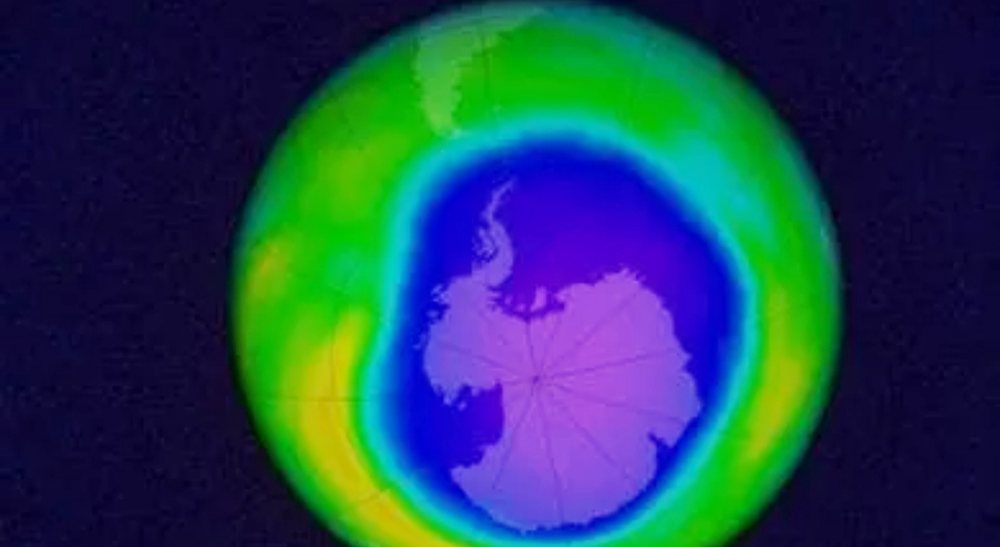

For some time now, the scientific community seems to be mostly in agreement that the "health" of the ozone layer in the stratosphere is gradually improving. And that's undoubtedly a good thing, since the ozone layer protects life on Earth from ultraviolet radiation emitted by the Sun. Things get complicated, however, when we consider the fact that ozone is also a greenhouse gas.

In this regard, the results of a study published in the journal Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics suggest that the "healing" of the ozone layer could contribute to global warming by about 40% more than previously predicted.

More specifically, the authors of the study have simulated through computer models how the atmosphere will change by 2050 and what effects these changes will have on the amount of heat trapped near the Earth's surface. The parameters used are intended to simulate a scenario with little implementation of air pollution measures, but at the same time with the gradual elimination of CFCs and HCFCs. The latter are gases that damage the ozone layer and, moreover, are greenhouse gases themselves. They are banned by the Montreal Protocol, which entered into force in 1989 and has been ratified by 197 countries, including Italy. Since then, the emission of ozone-depleting substances has been significantly limited.

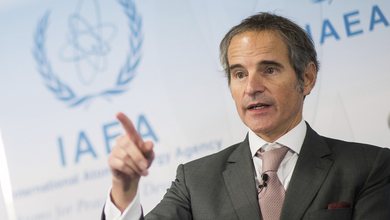

"Countries are doing the right thing by continuing to ban chemicals called CFCs and HCFCs that damage the Earth's ozone layer. However, while this helps repair the protective ozone layer, we have found that this ozone recovery will warm the planet more than we originally thought," explains Bill Collins, the study's first author and lecturer in the department of meteorology at the University of Reading (United Kingdom).

According to simulations, part of this contribution to global warming comes precisely from the restoration of the ozone layer in the stratosphere, and another part from the accumulation of ozone precursors (as a result of human activities, such as vehicle traffic and factory activity) in the part of the atmosphere closer to the Earth's surface.

The hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica appears to follow unusual trends.

However, protecting the ozone layer remains essential for human health, as well as for the protection of animals and plants. Exposure to high levels of ultraviolet radiation – those that are partially blocked by ozone – increases the risk of skin cancer, for example. A study published in 2024 in Global Change Biology also warned of the risk to animal species living in Antarctica if they are exposed to high levels of these radiations.

At the same time, this new research suggests that climate policies need to be updated to take into account the greater warming impact caused by the gradual improvement of the ozone layer.