Opinion from Muriel

The fall of Nicolás Maduro was not an exotic episode of Latin American politics. It was the predictable end of a model of power that extended beyond democratic boundaries, was personalized, protected by propaganda, and fueled by the informal economy of crime. This is the essence of the parallelism that Albania can no longer ignore.

Today, the debate is not whether Albania is Venezuela. The debate is whether it is following the same logic. And the signs are enough to raise alarm.

Long-term power and the transformation of the state into political property

Maduro did not fall as a self-proclaimed dictator. He fell as a leader who, step by step, shifted decision-making from institutions to himself. The courts, elections, the economy, security—everything was concentrated on a single axis. When checks and balances were eliminated, the state became fragile and vulnerable.

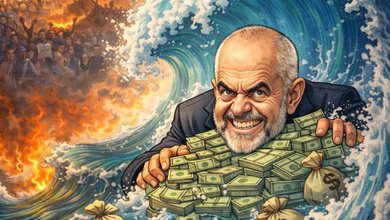

In Albania, Edi Rama’s rule has produced the same centralization effect: a prime minister as the focal point for every major decision; institutions that function formally but rarely challenge; a parliament that approves more than it checks; and a public perception that the electoral outcome is predetermined. This is not the standard of a functioning democracy—it is the personalization of power.

Propaganda instead of accountability

Maduro's shield was propaganda: relativizing failures, inventing enemies, communicative triumphalism over a reality that was collapsing. When transparency is replaced by narratives, power shifts from governance to survival.

Here too, criticism is stigmatized, scandals are scattered in the noise of communication, and failures are covered up with spectacle. This is a sign of strength only in appearance; in essence, it is a sign of political insecurity.

The gradual capture of the state

Maduro did not close down institutions; he rendered them harmless. The process was quiet, slow, but steady. In Albania, the symptoms are familiar: a politicized administration, an economically dependent media, self-censorship, and the dangerous belief that power is untouchable. This belief built Maduro’s “stability”—and that same belief brought him down.

Narco-economy: the point where parallelism becomes frightening

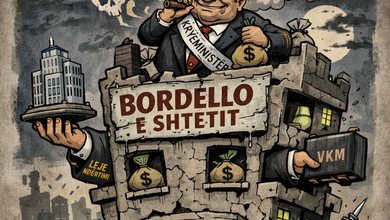

Venezuela collapsed when corruption and trafficking became a mechanism of governance. Not just peripheral crime, but an economic engine. Albania today faces an increasingly open debate on drug trafficking and narco-euros in the economy: informal money that inflates sectors, distorts competition, deforms the real estate market and creates political dependence.

When the real economy increasingly relies on the circulation of informal money, the state loses fiscal control, institutions weaken, and politics becomes vulnerable to criminal interests. At this point, the problem is not simply moral; it is structural. And the captured structures are not reformed—they are replaced.

Normalized corruption and the erosion of legitimacy

Maduro did not fall when scandals were revealed; he fell when corruption was perceived as the norm. In Albania, public perception has reached a dangerous threshold: tenders that are not explained, concessions that are not controlled, clientelism that is not hidden. When accountability disappears, legitimacy collapses—despite the rhetoric of stability.

The last illusion: "without me there is no stability"

“Without me, there is chaos” was Maduro’s final argument. Mild versions of the same thesis are heard wherever power equates itself with the state. History shows that stability without justice and without rotation is simply a delay in crisis.

The parallel with Venezuela is not an alarmist cry; it is a cold reading of power models. Long-term, personalized governments, protected by propaganda and fueled by the informal economy, lose the ability to correct themselves. At this stage, continuation does not bring stability—it brings higher costs for the state and society.

Maduro's fall is a reminder that no one is irreplaceable and that when signals are ignored, the end becomes harsher. For Albania, the message becomes clear: the longer political correction is postponed, the deeper the crisis that follows.