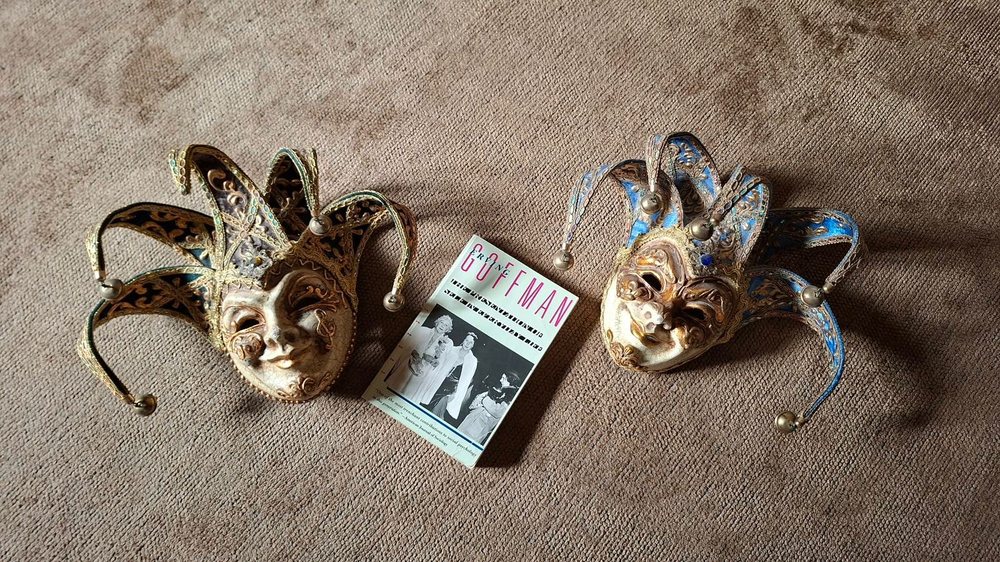

“When an individual enters the presence of others, they usually seek to obtain information about him or to play upon the information they already have about him… Thus informed, others will know how to act to elicit the desired reaction from him.”

— Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life

We are all actors and audiences at the same time.

In Goffman’s world, social life unfolds like a theater, where every entrance on stage carries expectations and every interaction is shaped by what is already “known.” We observe and react long before we are aware of it. This may seem harmless, but Goffman suggests that behind this behavior lies a deliberate script for performance.

For sometimes, what first enters the room is not the person, but the premeditated narrative. And once this narrative takes root, the interaction ceases to be spontaneous and begins to be managed, especially in the workplace.

This is where the puppeteer appears.

Not in a visible or dramatic way, because the puppeteer is rarely in the middle of the stage. He or she is a master of whispers and backstage innuendo, shaping perceptions before the new actor takes the stage, providing “context,” and presenting the newcomer not as a presence but as a potential problem.

Why does someone act this way?

Goffman gives us some clues. Social life depends on stability, and roles provide this stability. To assign someone a role is to limit their movement on stage, to decide in advance how a person will be read is to control how others will respond to them.

For the puppeteer, the new colleague or colleague is not simply a novelty. He or she is an unpredictable individual who poses a threat to the status quo or to existing privileges.

Unpredictability is threatening in spaces where personal relationships prevail over professional ones. It introduces uncertainty into carefully balanced performances. A competent newcomer can disrupt consolidated narratives. A new, confident presence can shift attention. A different way of speaking, thinking, or working can expose the mediocrity of existing roles.

For this reason, preemptively killing someone’s name is not an emotional reaction, but a strategic move that also requires the support of the puppeteer’s inner circle.

By writing the role for the newcomer from the beginning, the puppeteer reduces the risk to himself. The puppeteer sets up barriers around perception, ensuring that the natural curiosity of the team members turns into excessive caution and prejudice. The room is set. The audience knows what to look for.

And they act according to the script.

Questions are asked with subtext. Neutral behaviors are read through suspicion. Ordinary disagreement turns into evidence. The narrative begins to feed itself. What is surprising is how little effort is required, once the script is accepted.

Others believe they are observing objectively. They think they are “catching things.” They do not realize that they are reacting to signals already embedded in the scene. Goffman would say that they are acting rationally, based on the information they believe they possess.

The puppeteer no longer needs to be told. The strings now move on their own.

There is also a deeply psychological dimension at play here.

The puppeteer often acts to protect his or her self-image, the role he or she has carefully cultivated over the years. The arrival of someone new who is out of control, who is not part of the previous script, risks exposing the mediocre performance for what it is, jeopardizing the distinction between authority and insecurity, competence and control, talent and the “fake it until you make it” approach.

Therefore, the threat must be neutralized before it has time to show a different way of working.

This is why tactics are rarely direct. They rely on innuendo rather than accusation, on tone rather than fact, on repetition rather than evidence. The goal is not overt destruction but silent destabilization, the diminishment of the newcomer without ever showing the direct attack.

Goffman helps us see that this strategy is deliberate, related to human relations, but also structural, because its ultimate goal is related to who has the right to define reality on stage.

And once this definition is secured, the puppeteer can hide behind a performance of innocence. He or she has simply “shared concerns,” simply “reacted.” The audience has already adjusted expectations and fills in the rest on its own.

More disturbing is the ease with which a room full of intelligent people learns to doubt and the readiness with which seasoned professionals participate in a performance they did not write themselves.

Here, Goffman shows us that name-calling does not always stem from malice. Often, it stems from a fear of displacement, a fear of exposure, a fear of inadequacy, and a fear of being simply a fraud in the professional role. It is the fear of losing control over how the scene is read.

And perhaps the ultimate irony is this: the puppeteer believes she is maintaining order, while in reality she is exposing the inner pain and fragility of the scene itself.