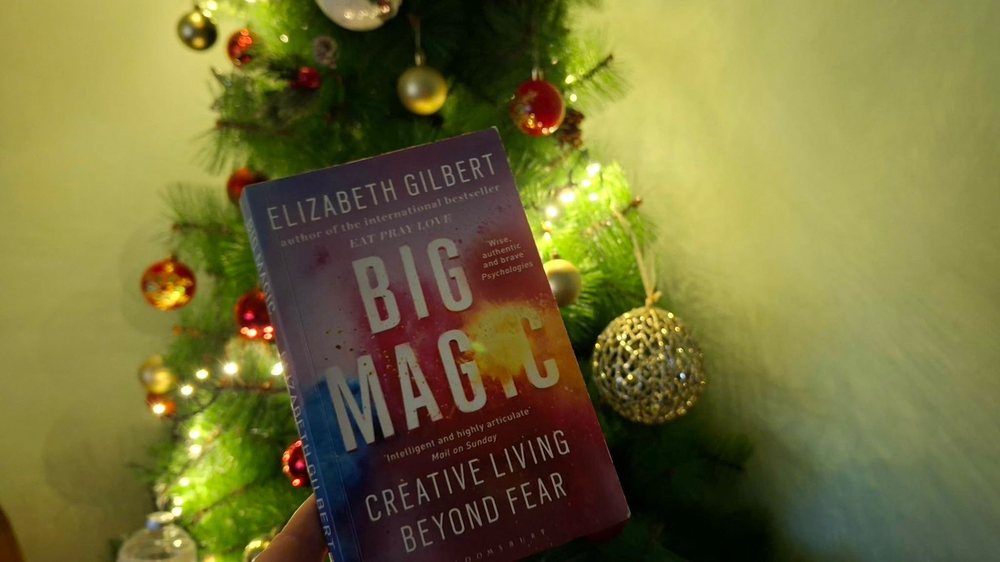

“You don’t need anyone’s permission to live a life of creativity.”

— Elizabeth Gilbert, Big Magic

There is a kind of fatigue that has nothing to do with sleep deprivation. That fatigue comes from holding ideas too tightly, from treating creativity as something that must justify its existence before it is allowed to breathe.

Elizabeth Gilbert’s Big Magic arrived as a gentle interruption to this fatigue. Not as a manual or a manifesto, but more like a voice saying, “You have a right to want this.” Gilbert treats ideas as living beings, wandering, curious, persistent, slightly impatient, constantly seeking people willing to collaborate, not suffer for them.

As we grow up, we learn the language of restraint. As individuals. In the workplace. In the world. Creativity is admired in theory but seen as destabilizing in practice. Truthfulness is graceful in art but inappropriate in boardrooms. We begin to polish the edges of our unique voice to fit expectations in the hope of getting written permission.

But waiting for permission is another form of self-punishment.

In her book, Gilbert invites us to invade our creative lives without seeking prior approval. She suggests that ideas don’t wait for credentials. Instead, they come to us hungry and unapologetic. They show up as uninvited guests, gently nibbling at us: “I thought you might want to create something.”

What if we thought of permission differently, as a skill to exercise, an internal compass to recalibrate?

In workplace communication, this matters. When we wait for permission to be creative and honest, we reduce communication to the lowest common denominator of safety: jargon, neutrality, and emotional flattening. We construct messages that avoid risk, rather than messages that invite resonance.

In professional life, especially in spaces shaped by fixed deadlines, constantly demanding justifications, logical frameworks, and frames of influence, creativity is often the first thing to become optional and requires a series of signed and stamped permissions. Something we promise ourselves “when things calm down.” But things never calm down. And the Great Magic suggests that suppressing creativity doesn’t make us more serious. It stifles our spark.

Permission to be curious, full of life, unfiltered in nuance, even with humor, changes what is said and how it is conveyed. It allows us to shape honest, not sterilized, narratives; to own our own ideas, not regurgitate what has been said and rehashed a billion times. It invites others to do the same.

Whenever I feel stuck in my creativity, I return to the Great Magic, which taught me that permission is not something that others give us. It is a conscious decision that must be made. That is where the turning point occurs, when we begin to experience creation as a relationship. Perhaps the real magic is to treat creativity as a companion on the journey.

There is something almost ethical about this attitude. It is to refuse to allow cynicism to masquerade as wisdom. To remember that ease is not the opposite of depth. Often, it is the gateway to it.