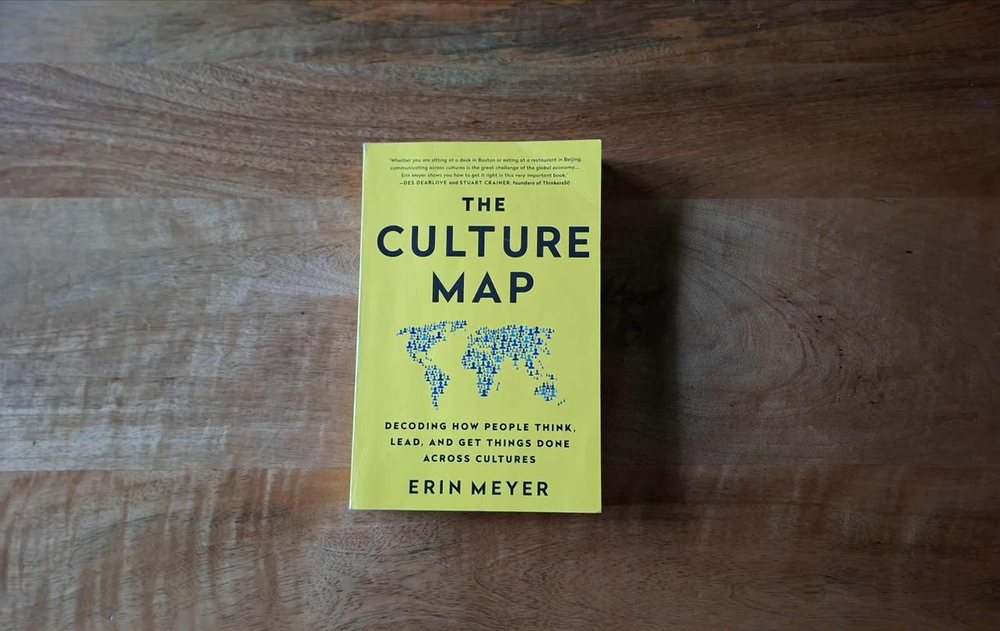

“When interacting with someone from another culture, try to look more, listen more, and talk less.”

— Culture Map, Erin Meyer

An old Albanian proverb says: “You have two ears and one mouth, so listen twice and speak once.” It may seem like advice to be modest and reserved, virtues prized in traditional societies. But, deciphered after years of lived experience, this saying is a gem of wisdom, because it emphasizes the power of active listening, or the key ingredient of effective communication.

In many workplaces today, especially multicultural ones, the act of listening is losing ground. Everyone speaks perfect English and uses industry jargon, presentations slide across screens, meetings are conducted with practiced confidence, but this fluency often masks a lack of listening. Beneath the surface of politeness and competence, something quieter but essential is lost: the art of listening to voices that are not your own, a lack of curiosity about what the other person brings to the table. It seems as if we all believe that our way of seeing the world is the right one, the best, the one that others should copy.

Erin Meyer, in her book The Culture Map, writes: “The way we are conditioned to see the world in our culture seems so natural and self-evident that it is hard to imagine that another culture could do things differently.” This sentence could hang on the wall of any office where the team is diverse. Because what one person calls clarity, somewhere else sounds like coldness. What is called “direct comments” can be perceived as public humiliation. Whereas silence, or submission to authority, can be a sign of genuine respect, or a gentle way to avoid unnecessary clashes.

Communication in international teams is not neutral ground. It is a landscape that favors the one who wields linguistic power, usually the person who is most comfortable with English, or appears most convinced that his way of working is the sacred model for others. So even when everyone is “fluent,” the balance of understanding remains uneven. Some sentences show attitude; others drift between the lines of culture, prejudice, and ego.

According to Meyer, communication lies on a map that moves from low to high context, from direct to indirect, from equality to hierarchy. But what intrigues me most is what these scales fail to measure: the emotional modesty to stop before finishing another person's thought, or before drawing conclusions without fully understanding the other person.

Is it really that hard to find the courage to say: "Maybe I didn't understand correctly? Can you explain it to me again?" Or is it that hard to listen to someone who speaks at a different pace, with a different way of articulation than you?

When the lack of listening occurs unintentionally, it is a habit that with a little awareness can be changed. But when the other person is deliberately interrupted, when his sentences are closed in a completely different way than he intended, that behavior is an act of aggression. Intercultural misunderstandings rarely explode, they slowly erode. Each such microaggression deepens the gap between intention and impact, while cooperation turns into a false choreography without rhythm, where everyone plays in a trance.

If we see the workplace today as an orchestra, the solution to achieving harmony lies not in louder voices or demeaning criticism, but in better listening.

In multicultural environments, listening is an ethical act. It requires each of us to remove ourselves from the center of definitions of intelligence, confidence, articulation, and professionalism. It reminds us that communication is not an individual performance, but a collective composition.

The advice of Albanian grandmothers, and also that of Meyer, to “listen twice and speak once” is seemingly simple. But, in essence, it is an invitation to presence without domination, curiosity without invasion. It invites us to treat every conversation as a translation, not as a transaction. To listen across cultures means to accept that no sentence has the same meaning twice.

And perhaps the true measure of fluency is not how perfectly we speak, but how willingly we know how to unlearn and relearn. Because the world outside our country of birth is just as beautiful and rich.