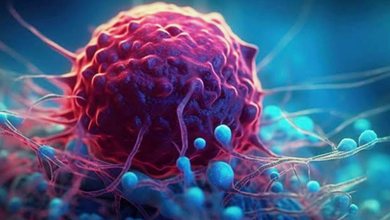

In a study conducted by researchers at the University of Leipzig and Shandong University, activating this receptor in mice triggered an increase in bone-building activity, strengthening both healthy bones and those affected by osteoporosis. The team focused on osteoblasts, the cells responsible for bone formation, and found that when the GPR133 gene was missing, the mice developed brittle bones that mimicked osteoporosis in humans. But when GPR133 was activated using a compound called AP503, bone strength improved significantly. This substance acts as a switch that turns on the activity of osteoblasts.

The compound AP503 was identified through computer modeling and worked even better when combined with physical activity.

This suggests that the treatment could be combined with lifestyle changes in the future to enhance its effects. Although the study was conducted in mice, the researchers say the mechanism is likely similar in humans, especially for postmenopausal women, who face a higher risk of bone density loss. Unlike current osteoporosis treatments, which often have side effects or lose their effectiveness over time, this approach shows promise in not only slowing bone loss but also actively rebuilding bone.

The discovery also points to broader uses: potentially to improve bone health before damage occurs, rather than just reversing existing damage.