More than 75 years after the end of World War II, Germany is still trying former members of the Nazi regime. Meanwhile, many others were never brought to justice for political reasons and because of German society's reluctance to confront its past.

After unconditional surrender in 1945, Germany faced a new reality: foreign occupation, total loss of power, and the collapse of its old belief in superiority. However, the biggest problem had to do with dealing with the crimes of Nazism—from 7.5 million party members, 850,000 SS members, to the shocking images of concentration camps that circulated around the world.

Nuremberg Trials

Allat had deep doubts that the Germans would be able to punish the Nazi criminals themselves. For this reason, in 1945 the International Military Tribunal was created, which held the famous Nuremberg trials. From November 1945 to October 1946, 22 leading figures of the Third Reich were tried, including Göring, Hess and Ribbentrop. Twelve of them were sentenced to death.

Less well-known is the fact that between 1946 and 1949, 12 other major trials were held in Nuremberg, including the trial of camp doctors, the heads of giant companies such as Krupp and IG Farben, and investigations into the main structures of the SS. The last execution for Nazi crimes in Germany was carried out in 1951.

Restraining punishments and the policy of silence

With the creation of the Federal Republic of Germany in 1949, the political climate changed. Chancellor Konrad Adenauer supported a quiet approach to the past, reinstating thousands of former Nazis and enabling many of them to avoid criminal responsibility. In the 1950s, trials for Nazi crimes were drastically reduced.

The new generation and breaking the wall of silence

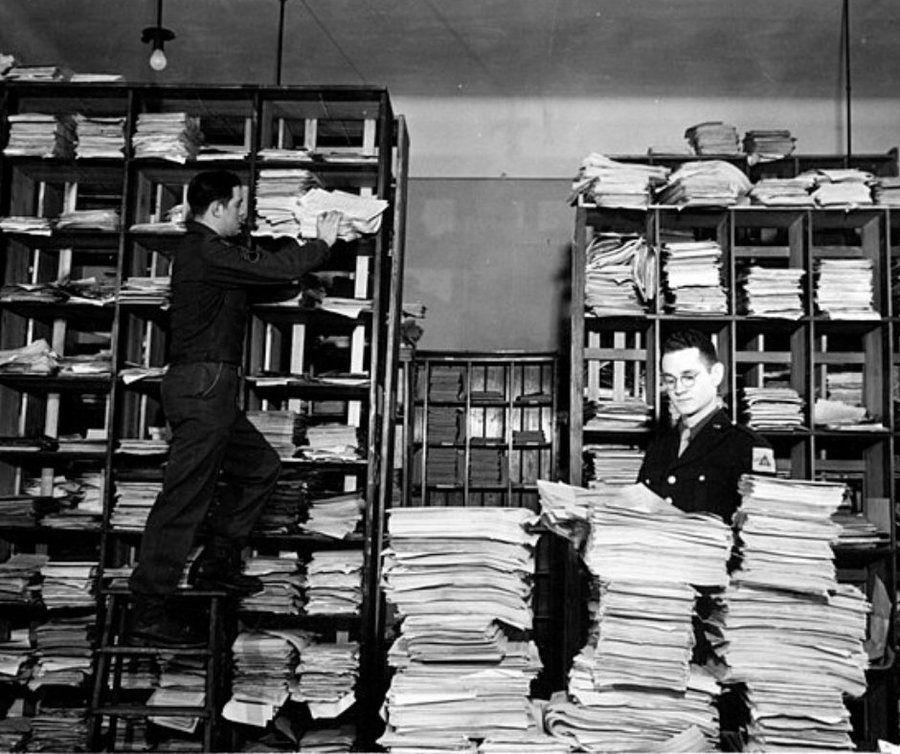

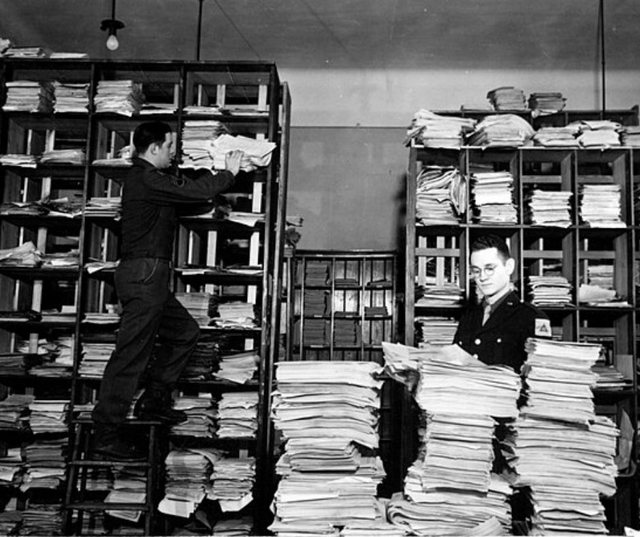

In the late 1950s, the younger generation of Germans began to earnestly seek to shed light on the past. This led to the creation of the Central Office for the Investigation of Nazi Crimes in Ludwigsburg, which has prepared over 7,500 indictments to date.

Another turning point came with the television broadcasts of the trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1961 and, subsequently, with the great Auschwitz trial in Frankfurt (1963–1965), where 20 camp employees were tried.

However, legal restrictions and narrow interpretations of individual responsibility meant that many mid- and high-level perpetrators received low sentences or were not tried at all.

The fight for the statute of limitations on crimes

A fierce political battle took place over the statute of limitations for Nazi crimes. It was not until 1979, after international pressure and the strong influence of the American series Holocaust, that the German parliament decided that the murders committed by the Nazis would not have a statute of limitations.

The Last Judgments – Justice That Comes Late

Even in recent years, new processes have been developed:

In 2009, former officer Josef Scheungraber was convicted.

In 2011, former Sobibor guard John Demjanjuk was convicted.

Today, several trials of very elderly people are still ongoing.

Critics point out that most of the top commanders are now dead, while only low-ranking individuals face justice today. However, the fact that Germany continues to punish Nazi crimes despite the passage of time is considered unique in modern history.