A single glance carries immense power. The moment you are under the gaze, you become more than yourself; you become someone else's judgment.

What happens to human dignity when the way others look at you turns you into a label or a body, turns you into an object of observation or ridicule, or worse, gives you the deliberate message that you are invisible, therefore unimportant? The energy that the gaze carries shapes perceptions. It can define or wound, magnify judgment or give life to the knowledge of the other.

The gaze has several dimensions. Spiritually, it is never neutral, as it reflects the state of the heart and precedes intention and then action. In the ethical dimension, it carries responsibility. The way we look at others can affirm their dignity or diminish it. In the social dimension, it functions as the invisible language that determines norms and power relations.

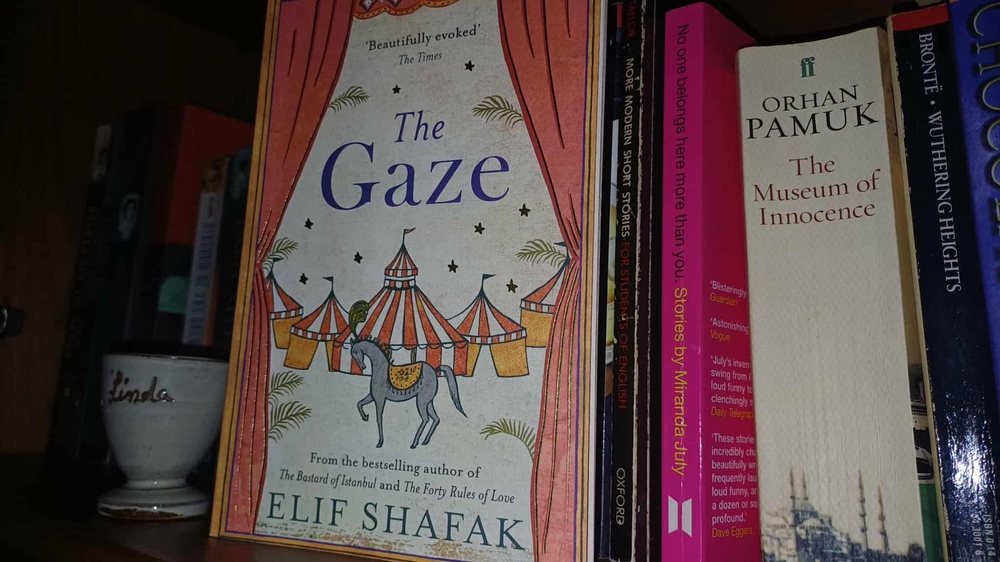

Reading the book “The Gaze” by Elif Shafak, I realized how the stories within it shed light on the violence of perception. It is a book about eyes: who is being looked at, how they are being looked at, and how much of themselves are lost in the process. Shafak’s characters live under constant surveillance, just as people in the workplace are. In her novel, the gaze is rarely gentle, just as in the workplace. The gaze is the mirror that magnifies cruelty, a reflector that turns people into curiosities, a silent judgment that wounds and defines, just as in the workplace.

This kind of judgment that arises from the seemingly simple act of looking is all too familiar in the workplace, where the gaze is everywhere. It's not just about physical bodies, or performance appraisals, but also about how ability, ambition, differences, or personal style are observed. The look that lingers a little longer when you're wrong. The irony when a woman over 40 suggests something. The deliberately raised eyebrow that turns your contribution into a question mark. The way some people are looked at to confirm, others to correct. The pain of the disdainful looks that a group throws at you and you accidentally see them. The calculated look when they need something from you.

These looks accumulate and show you how little or how much you belong to a place or how valued you are as a being. The danger lies not only when you are openly ridiculed or turned into an object, but also when you are seen through a lens that reduces you to a single dimension: “the woman who is too persistent”, “the man who is too silent”, “the colleague who is only good for one thing”, “the stylish young girl who is only for eyes” and so on. In these moments, the gaze is not neutral, it becomes a framing lens and a form of control that reduces a person to something less than whole.

But the gaze can also be used to give life to belonging, recognition, support, and solidarity, just as it can reinforce exclusion and hierarchy. The gaze I am talking about is not about seeing, but about presence, about knowing, and about the quiet but profound way in which we shape each other's realities.

The way we choose to look at others has as much power as the way they look at us. In some workplaces, the gaze becomes a weapon to humiliate, to exclude, to turn colleagues into objects of observation rather than subjects of respect, into individuals with their own worlds and lives. In other settings, the gaze is a gift, an act that listens rather than judges, becomes an energy that affirms rather than erases.

Looking with respect can humanize. Looking with curiosity can expand the capacity for understanding. Looking with acceptance can restore someone who has been humbled by ridicule or disregard.

Shafak's novel is about the power of the gaze. He reminds us that each of us has eyes that can wound or grant dignity. Seeing is a choice. Looking with respect can change the energy of a room. Looking with interest can open the door to conversation. Looking with acceptance can restore dignity to someone who has been left aside.

In the workplace, as in life, the way we look at others may be the most underrated form of communication. Are we paying attention to what our gaze communicates?

Can we choose to see one more time?

⸻