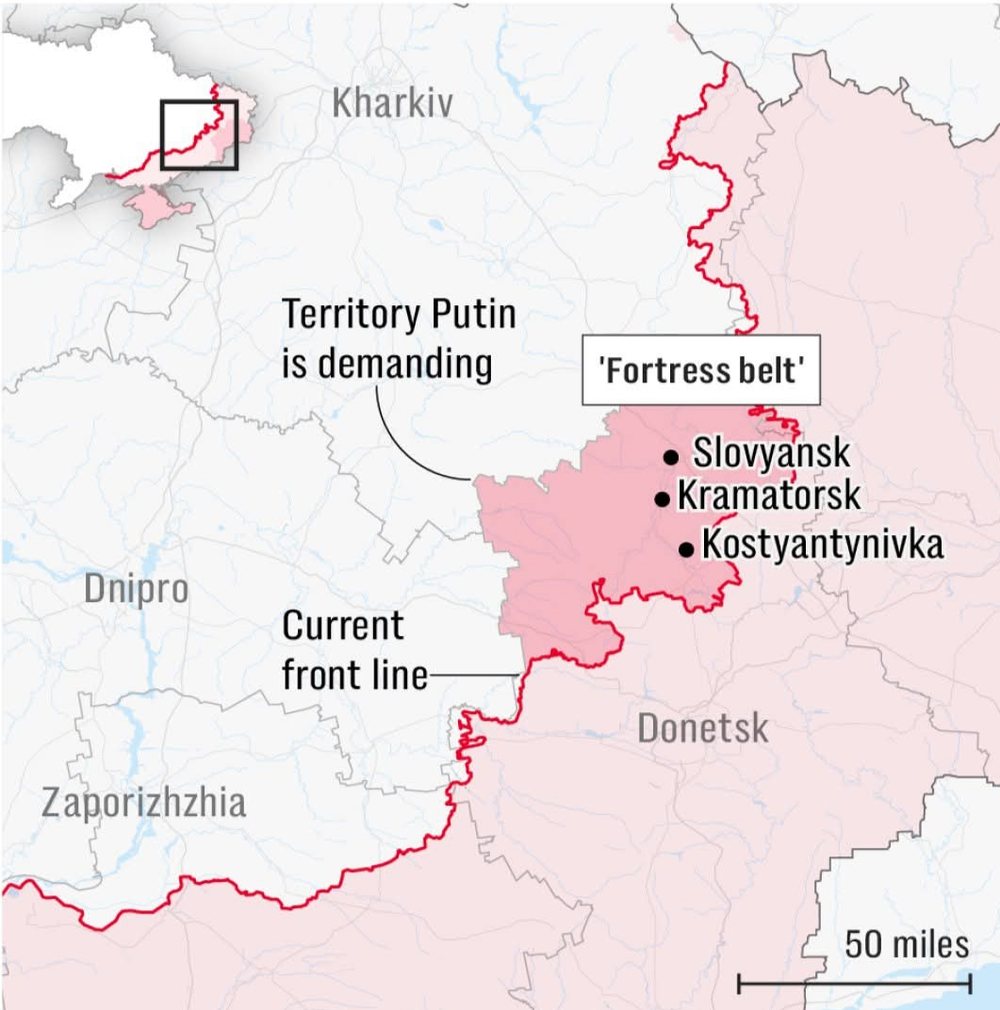

Russian President Vladimir Putin wants to take over the Donetsk Suffrage Belt. He has made it clear that he wants the entire Donetsk region as the price for peace. Here's why Ukraine refuses to hand it over.

Although the Kazenyi Torets River flows through four major cities and is bounded by a railway and a road, you can travel along its entire valley without even noticing it. Hidden for most of its length by a thick belt of swampy forest on both banks, its waters are usually left to kingfishers and frogs.

But, most importantly, this placid river runs through the center of the last quarter of the Donetsk region held by Ukraine, and the string of towns on its banks has been transformed into a fortress – a nearly impregnable fortification that has withstood Russian attacks for more than a decade.

Eleven years ago, I watched the war in Ukraine begin on its banks. Three years ago, I sat by the river again and wondered if this would be the last time I would see it, as the Russian bombardment drew near. Now, it is at the heart of contentious negotiations to end the war.

The Kazenyi Torets River in Donetsk

Vladimir Putin has included the entire Donetsk region in the Russian constitution and has made it clear that he wants the entire region — especially this last, bold scoop — as the price for peace. Donald Trump seems willing to push Volodymyr Zelensky to make such a deal.

Steve Witkoff, Mr. Trump's special envoy for Russia, said on Sunday that there would be a "significant" and "very detailed" discussion about the fate of the Donetsk region when Mr. Zelensky arrives in Washington on Monday.

Mr. Zelensky is reluctant: “Russia still has no success in the Donetsk region, and Putin has not been able to take it for 12 years,” he said on Sunday, adding that discussions about territory swaps there are so important that they should only be discussed bilaterally between Ukraine and Russia.

To understand why Russia wants it so badly and why Ukraine refuses to hand it over, it's worth looking at a map. Here's why the "Donetsk Fortress" matters:

territory

At the upper part of the valley, at its southern mouth, lies the town of Kostiantynivka. Then come Druzhkivka; Kramatorsk; and finally Sloviansk, where the river turns east before passing through a floodplain of bushes and reservoirs until it meets the Siversky Donets River – the main river of the Donbass.

In fact, the very word Donbass – used to describe the coal-rich eastern part of Ukraine, now partially occupied by Russia – is an abbreviation for “Donets Basin.” Ironically, the area’s geological past makes this part of the basin actually a mountainous area. And as a mountainous area in a vast plain, it has great strategic and military importance.

As if that weren’t enough, these aren’t the Himalayas; the highest point is just over 300 meters above sea level, and the slope is so gradual that if you’re not paying attention, you won’t notice it. But it is a mountainous area nonetheless – a network of mountains and valleys rising above the Pontic Steppe that dominates the southern half of Ukraine and Russia.

The Torets River cuts a valley at the northwestern edge of this highland. On its right bank in particular, the land rises rapidly to a hill where the town of Chasiv Yar and the actual front of the war are located.

Today, those slopes and hills are filled with Ukrainian defensive lines built over more than a decade. The slopes have been measured, the killing spaces have been measured, the elevations and depressions of the land have been integrated into killing zones and artillery ranges.

In other words, it is a bulwark that protects the entrance to the heart of Ukraine, protecting it. Not only that, but it is a bastion that protects the entire current front line. If it falls – or surrenders – not only does the Ukrainian steppe open up behind it, but Russian forces would have a platform to encircle Ukrainian forces both to the northeast, in Kharkiv, and to the south, in Zaporizhzhia. If Ukraine is forced to surrender, then holding the front line, or even defending the rest of the country, will be much more difficult in case Russia decides to attack again and take the territory that Putin still calls “Novorossiya” – New Russia.

inFRAStRuctuRe

After all, armies are large groups of people. And like any large group of people, they need places to sleep. And places to eat. They need transportation, fuel, hospitals and cafeterias, and all the things most of us take for granted. In other words, they need a city.

When Ukraine lost control of Donetsk, the regional capital, in 2014, it was left at a huge disadvantage: the enemy possessed the most advanced and comfortable set of infrastructure between the Russian border and the central Ukrainian city of Dnipro. Ukrainians were left with surrounding villages that were economically dependent on the big city.

The small towns of Kramatorsk, Sloviansk, Druzhkivka and Kostiantynivka were the best option. It was an abandoned post-Soviet landscape: a dilapidated glass factory that once produced the stars to adorn the Kremlin’s spire; distant piles of waste from mining towns; towns mostly made up of small houses where many people lived off their gardens; a road connecting them that even before the war was in dire need of repair.

But with a main railway and a highway connecting all four cities to Kharkiv and Kiev, the valley was convenient for logistics, supplies and medical treatment. And there was a sufficient local economy for the army's needs: from supermarkets to pizzerias and gas stations.

Over time, this conurbation – cities that often seem to merge into a single road – became a fortress and an economic and logistical hub. The Kramatorsk air base, located on the eastern hill of the city, became the command center for the low-level war that lasted eight years from 2014 to 2022.

This was not without tension. The influx of soldiers caused problems. Part of the local population was always sympathetic to Russia. Even after the complete occupation, it was possible to meet residents who jokingly admitted that their opinions had not changed.

Since the beginning of the occupation, the cities have assumed even greater importance. Kostiantynivka was the logistical center to support Bakhmut, Chasiv Yar, and Toretsk during the Russian attacks on them. Further north, Sloviansk and Kramatorsk served as the rear area for the battles around Lyman, Izyum, and the ongoing war in the Siversk area.

If the valley falls, the Ukrainians don't just lose fortifications and advantageous positions; they lose the urban infrastructure and logistics that make it possible to maintain the army and defend.

And don't forget the several hundred thousand civilians living in this hollow. Many of them have returned even after fleeing at the start of the full-scale occupation, thinking that Kramatorsk is at least as safe – or safer – than other parts of the country.

The towns of possible future defense – Izyum and Bavinkove in the Kharkiv region, Petropavlivka in the Dnipropetrovsk region – are dozens of miles away or will remain undefended, with their flanks exposed, if the Torets Valley fortress falls.

History

Putin's interest in this corner of Donbas is partly political: he has told the Russian public that his goal is to liberate the entire Donetsk and Luhansk regions, so he must capture it in order to claim a real victory.

Not since French General Robert Nivelle declared "the Germans will not pass" at Verdun has a fortress city taken on such political, emotional and strategic significance.

This is where the Russian-Ukrainian war actually began – in April 2014, when a small group of heavily armed terrorists, led by a Russian intelligence officer named Igor Girkin, attacked the city hall, police station, and secret service office in Sloviansk. They then moved on to other cities through the hills and valleys, attacking police stations, kidnapping, torturing, and killing their opponents.

Two of their victims – local councilor Volodymyr Rybak and a teenage activist named Yuri Poporavka – were tortured to death and thrown into the Torets River.

The Ukrainian recapture of Sloviansk and the entire Torets Valley in June of that year was their first major success in the war – in fact, the first time the Ukrainian army proved that it could withstand and defeat Russian-led forces.

Since then, Sloviansk has become symbolic for both sides. For Russians, it is the birthplace of the FSB-orchestrated “rebellion” that served as a justification for the invasion. For Ukrainians, it is ground zero of their battle for national survival. The legend has grown 1,000-fold since the full invasion.

In the summer of 2022, the Ukrainians stubbornly resisted a Russian attempt to attack the fortress from two sides. The enemy approached Sloviansk from the north, the sound of Russian artillery getting closer day by day. But they failed to enter the fortress before being met with a Ukrainian counterattack.

Since then, Russian operations – from the nine-month battle for Bakhmut to the current attacks on Pokrovsk and Toretsk – have been directed primarily against Kostiantynivka, Druzhkivka, Kramatorsk, and Sloviansk.

Many Ukrainians have died defending and holding the cities of the fortified belt; many men and women from all over Ukraine know the spoon and its potholed highway; many have stopped for their last coffee before the front at gas stations, so surrender is almost unthinkable.

The Guardian