The letter published below, recently discovered in the archival funds, is one of the many testimonies of the fate of intellectuals persecuted in communist Albania. Gjergj Komnino, initially sentenced to death after daring to write a letter to the UN about the mistreatment in communist Albania, wrote several letters from prison to Prime Minister Mehmet Shehu with the request to save his literary and scholarly manuscripts created before and during his imprisonment, but whose fate was unknown, as they had been seized by the State Security. A letter written by him contains notes of sarcasm towards the regime, while the pain for his family and two-year-old son was great.

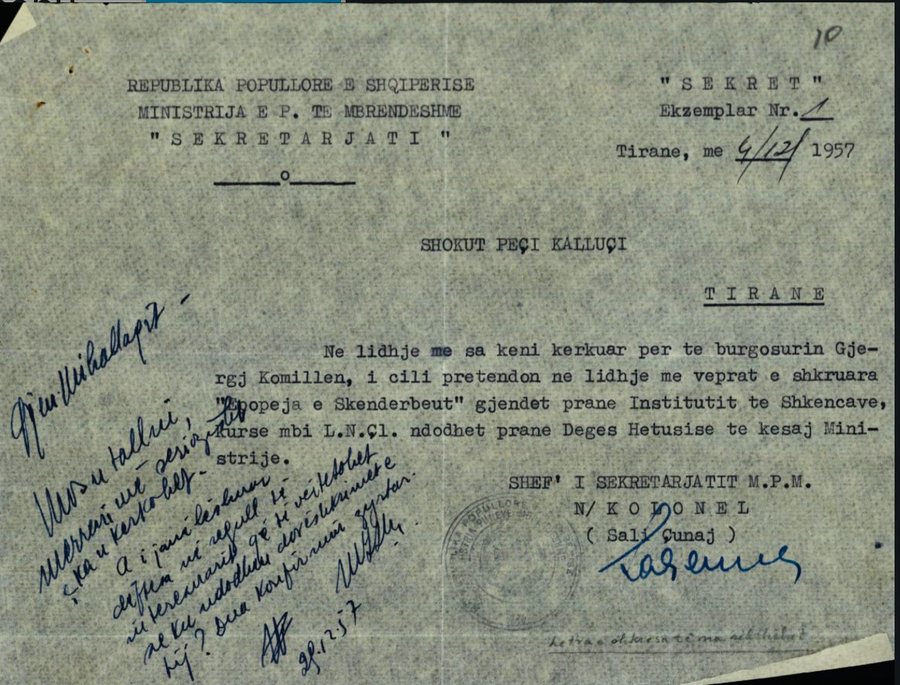

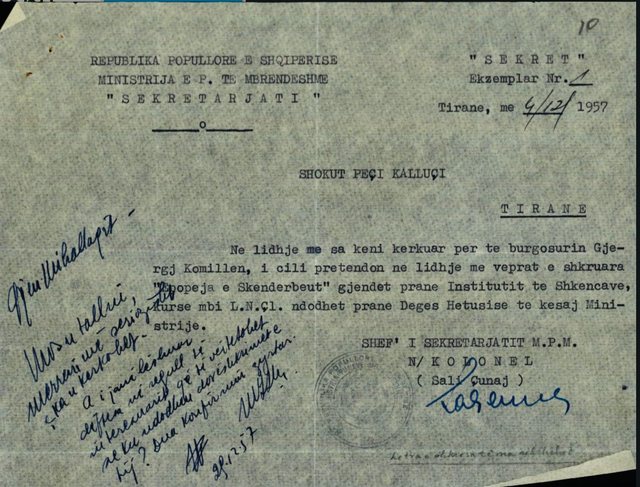

The letter we are publishing was written in 1958, while Prime Minister Shehu himself, who always clashed with the Minister of the Interior, Kadri Hasbiu, in one of his commentaries on the fate of the Komnino manuscripts, requested that the issue be treated seriously.

"Gen. Mihallaq! Don't joke. Take what was asked of you seriously. Have the proper receipts been issued to the interested party to verify where his manuscripts are located. I want official confirmation!"

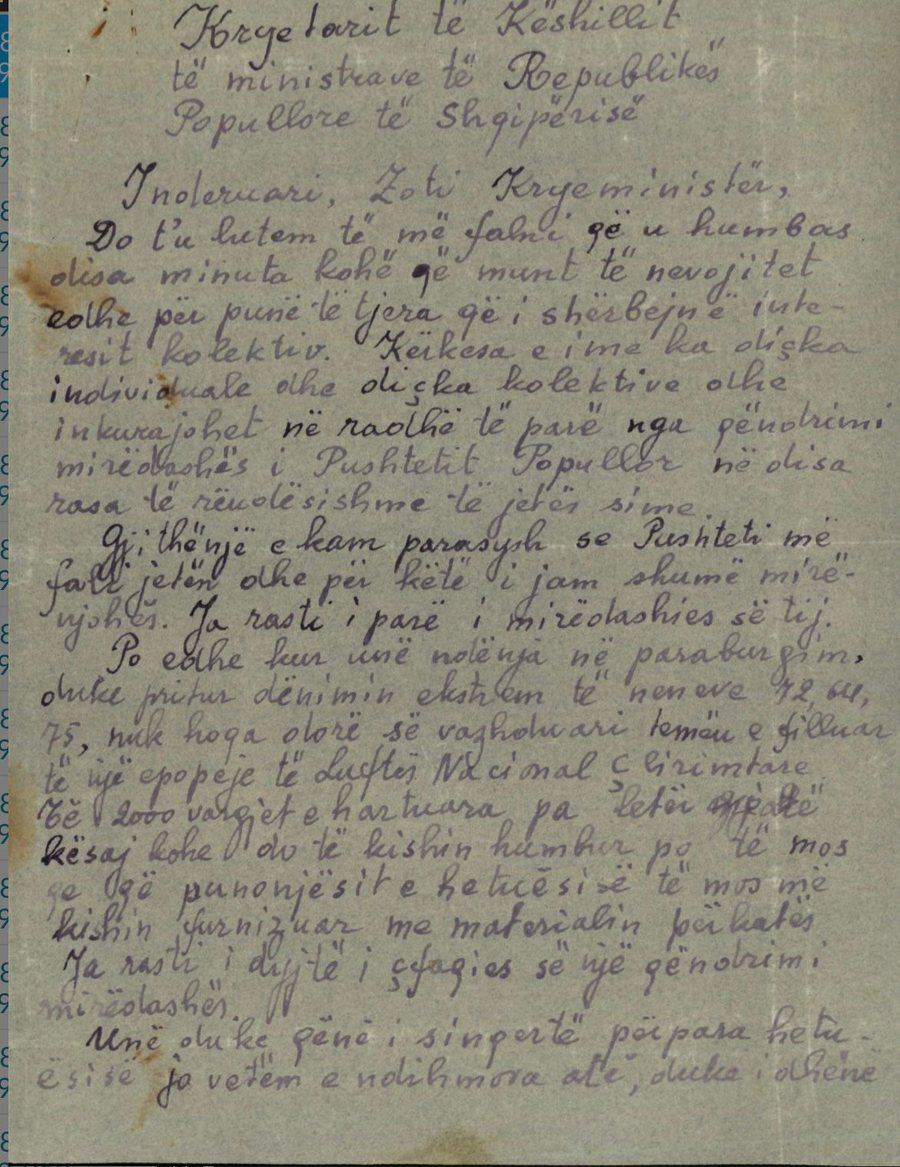

Gjergj Komnino's letter to Mehmet Shehu (1958)

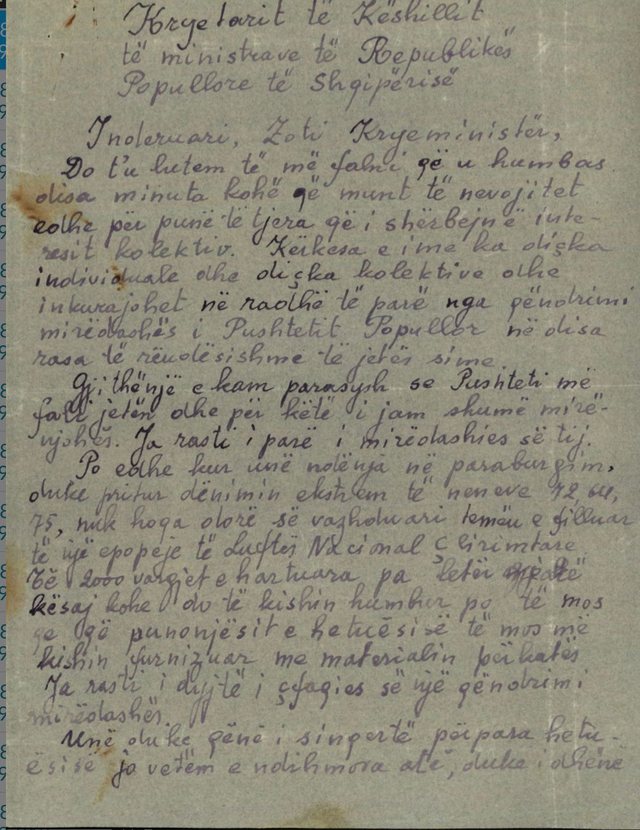

The Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Republic of Albania.

Dear Mr. Prime Minister.

I would like to ask you to forgive me for wasting a few minutes of time that could be needed for other tasks that serve the collective interest. My request has something individual and something collective and is encouraged in the first place by the compassionate attitude of the popular government in several important cases of my life.

I always keep in mind that the government spared my life and for that I am very grateful. This is the first instance of its mercy.

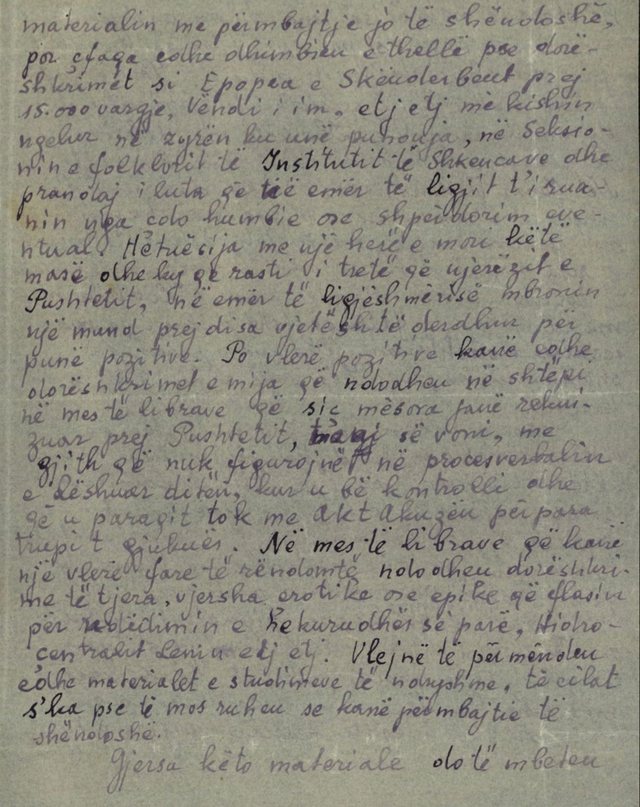

Even when I was in custody, awaiting the extreme punishment of articles 72, 64, 75, I did not give up because I continued the theme of an epic of the national liberation war that I had begun. The 2000 verses compiled without paper during this time would have been lost if the investigation officers had not supplied me with the relevant material. Here is the second case of joy from a merciful attitude.

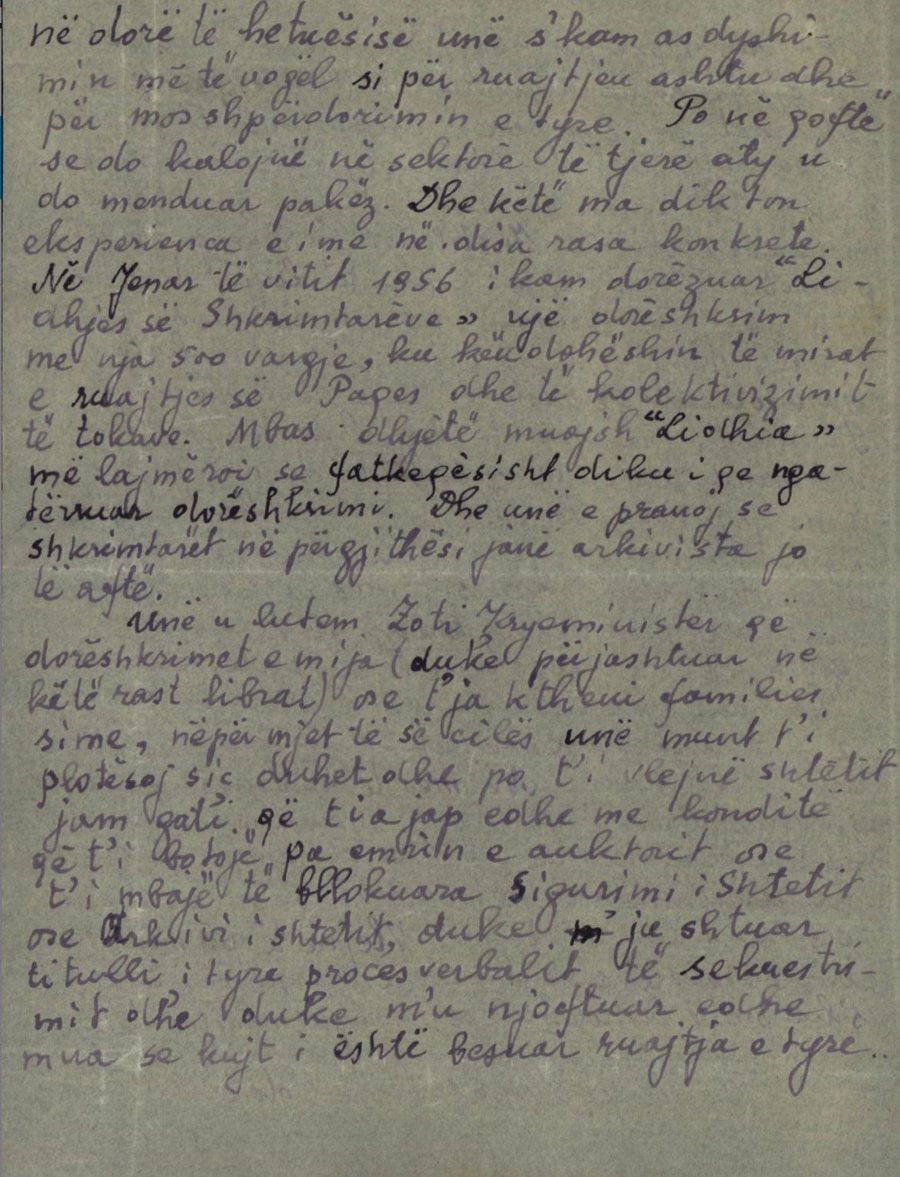

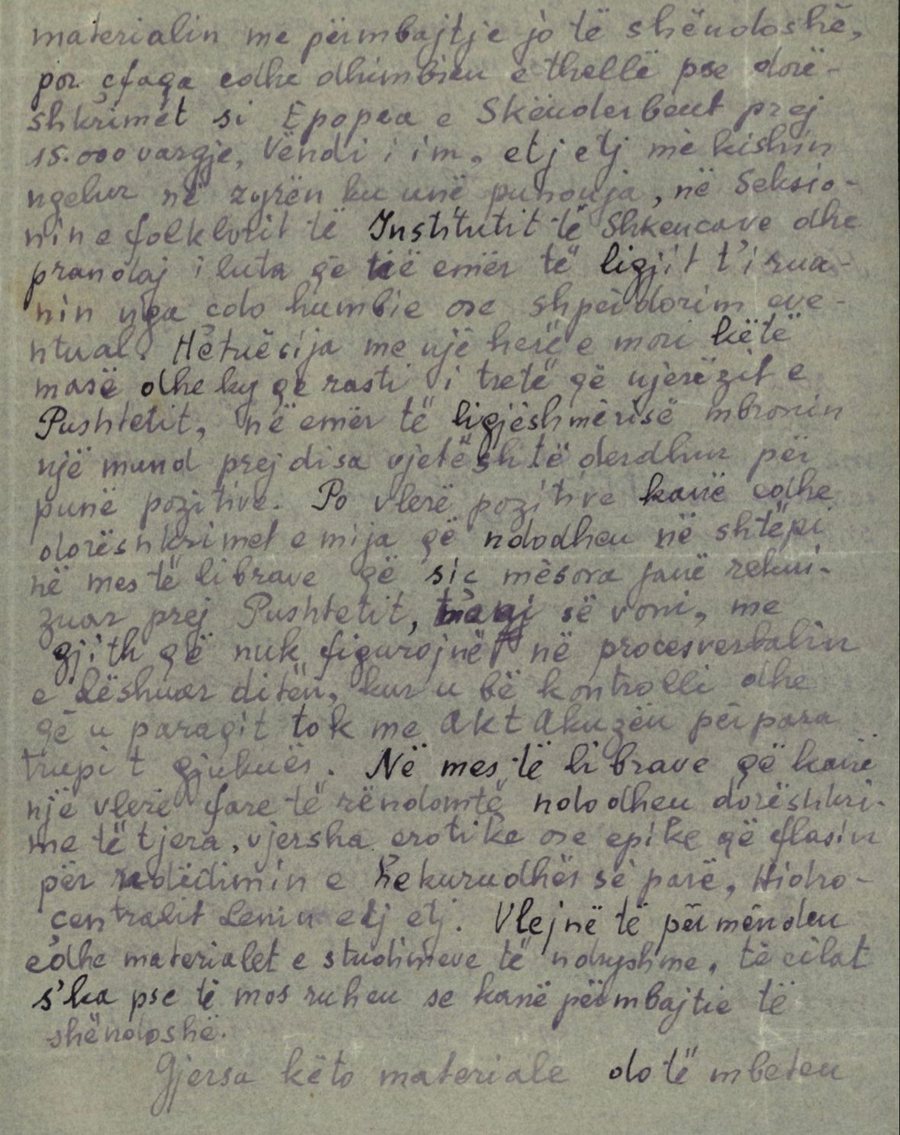

Being honest before the investigator, I not only helped him, by giving him material with unhealthy content, but I also found deep pain because manuscripts such as the 15,000-verse Epic of Skanderbeg, My Country, etc., etc., had remained in my office where I worked, in the folklore section of the Institute of Sciences, and therefore, I asked them to protect them in the name of the law from any eventual loss or misuse. The investigator immediately took this measure and this was the third case that people in power, in the name of legality, protect a few years of effort spent on positive work. My manuscripts that are at home with the titles of books that, as I learned, were recently requisitioned by the authorities, also have positive value, even though they do not appear in the report issued on the day the inspection was carried out and that was presented together with the indictment before the court. Among the books that have a very ordinary value are other manuscripts, erotic or epic poems that talk about the construction of the first railway, the Lenin hydroelectric power plant, etc. It is also worth mentioning the materials of various studies, which should not be preserved because they have sound content.

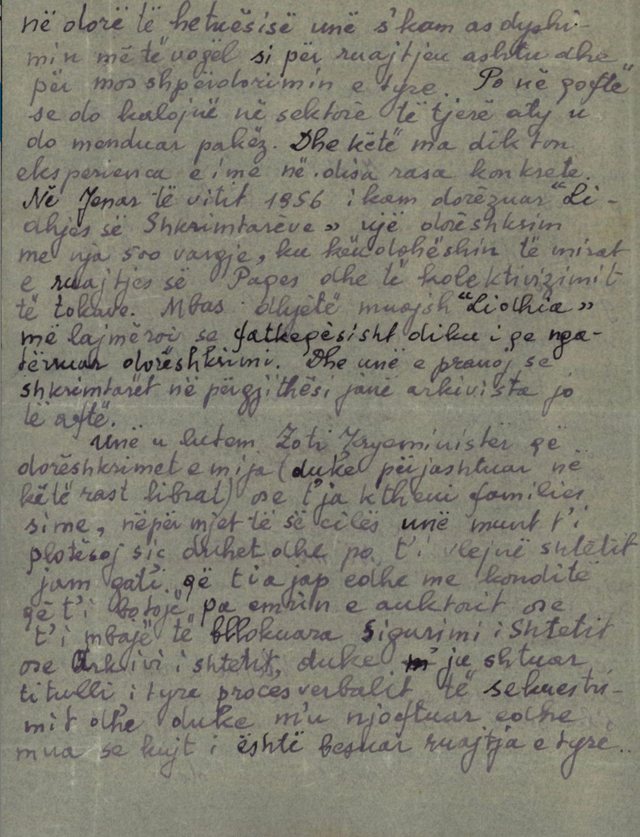

As long as these materials will remain in the hands of the investigation, I have no doubt about their preservation and not being misused. But if they are to be transferred to other sectors, I will give them a little thought. And this is dictated to me by my experience in several specific cases. In January 1956, I submitted to the “League of Writers” a manuscript with about 500 verses, where the benefits of preserving wages and collectivization of land were sung. After ten months, the “League” informed me that unfortunately the manuscript had been mixed up somewhere. And I admit that writers are generally incompetent archivists.

I beg the Prime Minister to either return my manuscripts (excluding the books in this case) to my family, through whom I can complete them properly, and if they are of value to the state, I am ready to give them to it on the condition that it publish them, without the author's name, or that the State Security or the State Archives keep them blocked, adding their title to the seizure record and informing me as well as who has been entrusted with their safekeeping.

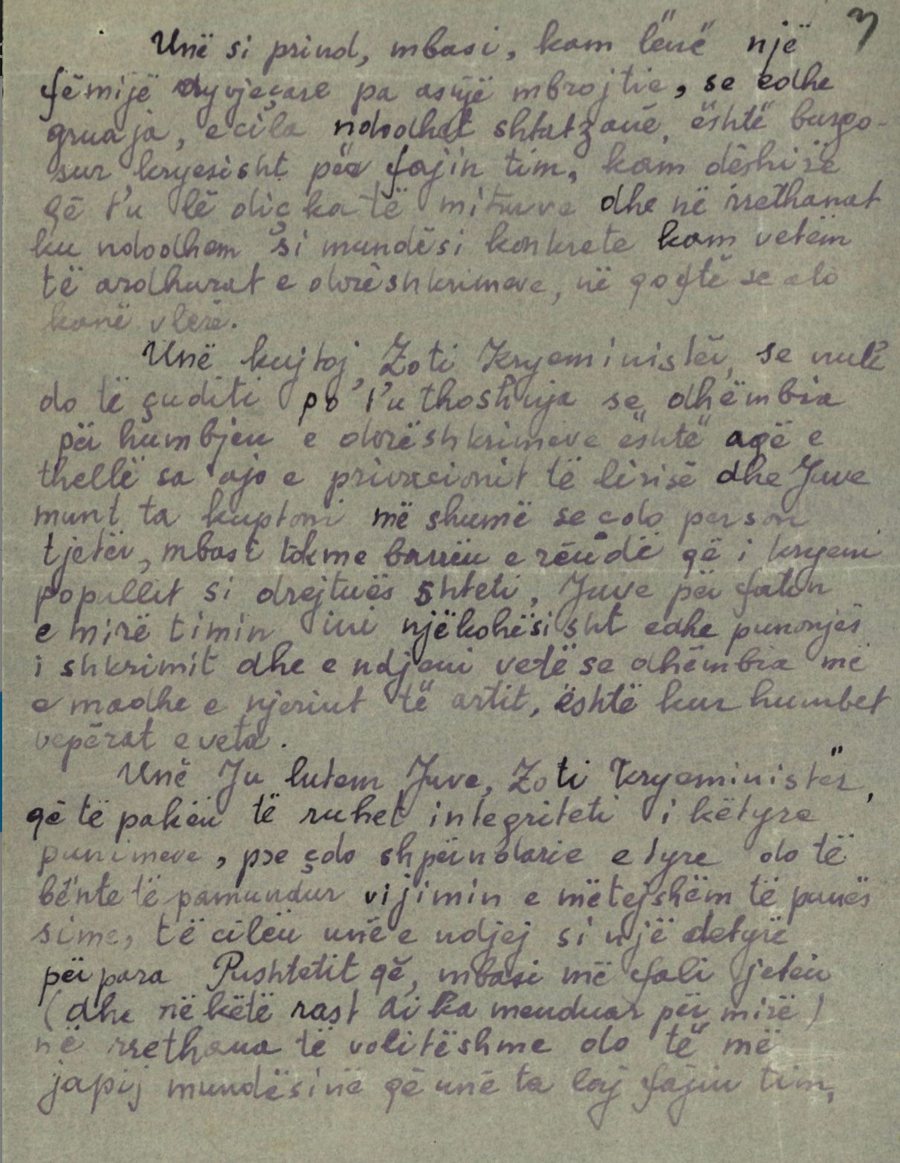

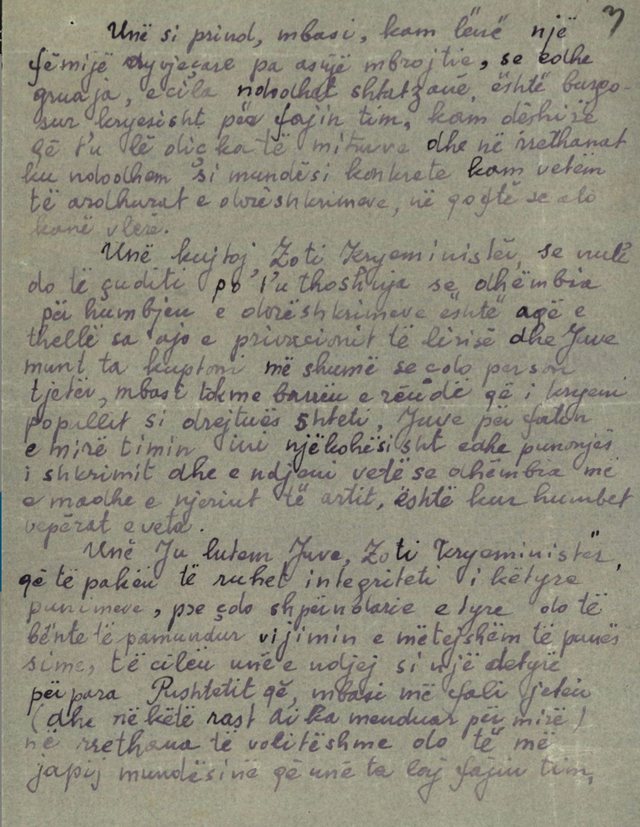

As a parent, having left a two-year-old child without any support, and my pregnant wife being imprisoned largely because of me, I would like to leave something to the minors, and in the circumstances I find myself in, the only concrete option I have is the income from the manuscripts, if they have any value.

I remember, Mr. Prime Minister, that it would not be surprising if I said that the pain of losing manuscripts is as deep as that of deprivation of freedom, and you can understand it more than any other person, since along with the heavy burden you carry for the people as a leader, you are, fortunately for me, also a writer, and you feel for yourself that the greatest pain of a man of art is when he loses his own works.

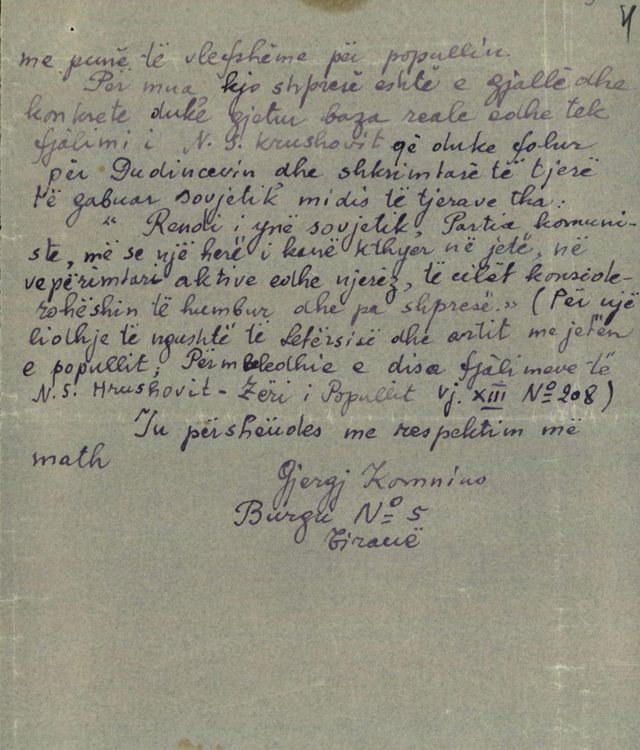

I beg you, Mr. Prime Minister, to at least preserve the integrity of these works, because any distribution of them would make it impossible to continue my work, which I feel is a duty to the government that, after sparing my life (and in this case it meant well), will, under favorable circumstances, give me the opportunity to atone for my guilt with valuable work for the people.

For me, this hope is alive and concrete, finding real basis even in the words of NS Khrushchev who, speaking about Dudince and other erroneous Soviet writers, among others, said:

“Our Soviet order, the Communist Party, has more than once brought back to life, to active activity, even people who were considered lost and hopeless.” (On a close connection of literature and art with the life of the people; collection of several speeches by NS Khrushchev – Voice of the People Vol. XIII No. 208).

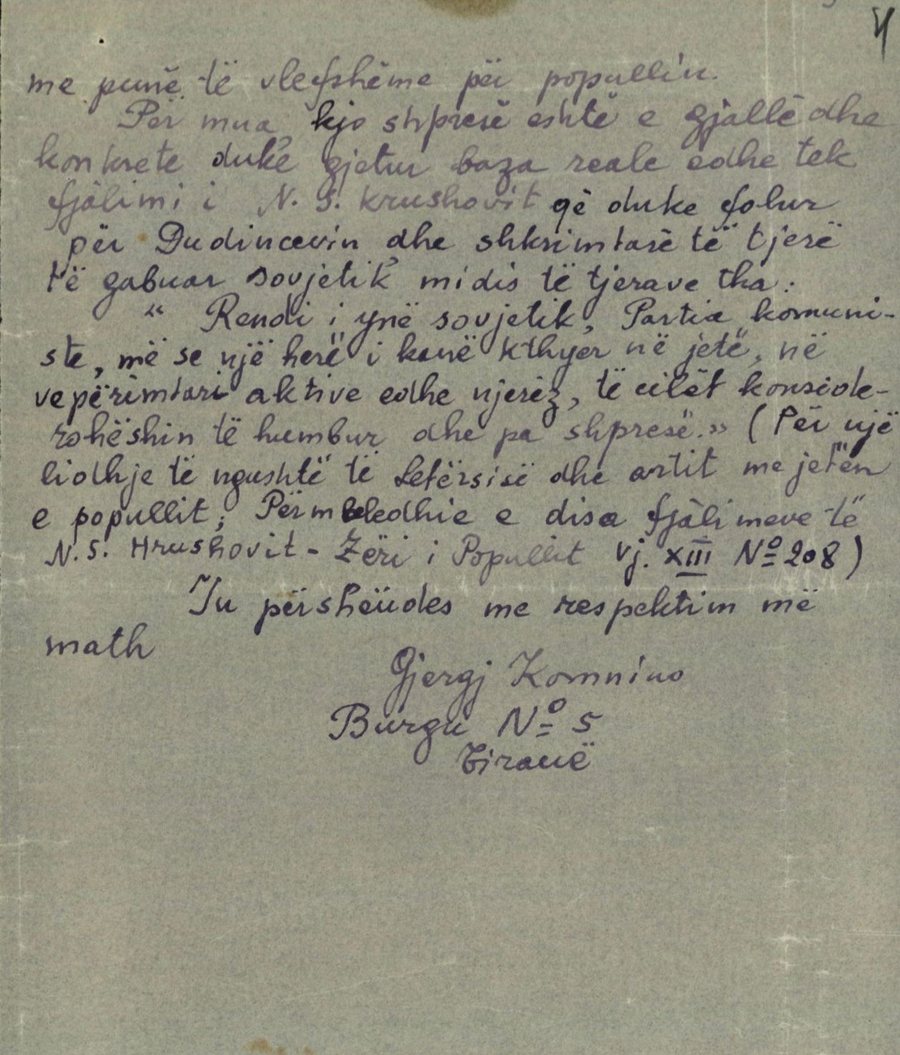

I greet you with the greatest respect.

George Komino

Prison No. 5 Tirana