By Desada Metaj

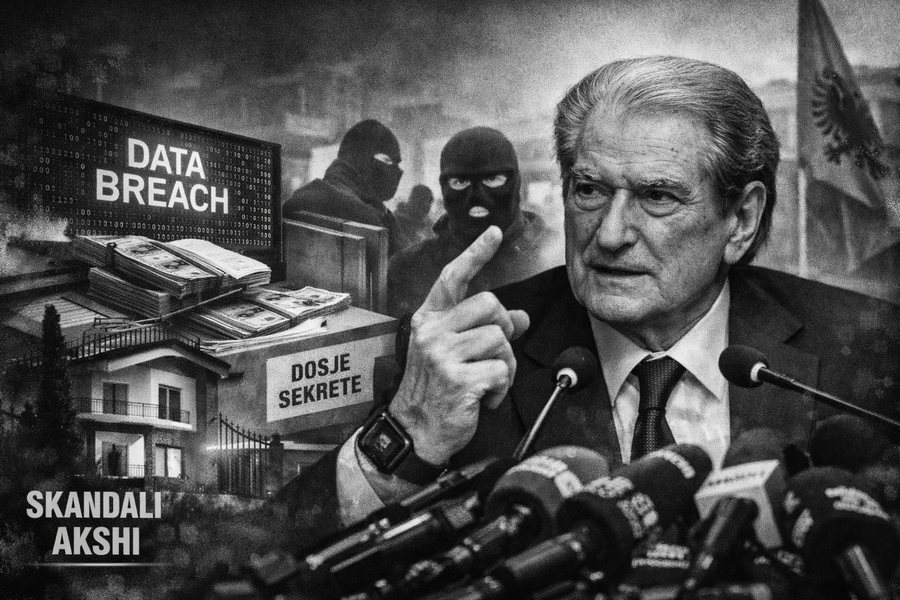

The most efficient way to trivialize the scandal of the AKSH tenders and the real endangerment of Albanians' data was Sali Berisha's press conference. Not silence. Not the lack of reaction. But precisely the public outcry.

In one of the most serious and blatant crises that can happen to a government in a country that claims to be European, the leader of the divided opposition chose today to deal with the fines for Ergys Agas's car near Edi Rama's house in Surrel. From a state scandal of systemic proportions, the matter was reduced to a provincial giallo, easy to consume, but useless to understand.

Making a “thriller” with the Agasi file in a country like Albania, where crime and politics are intertwined to the core, is simple and tempting for a weary public. But is this the message that the main opposition party should give? What does the public gain from the epithets that Sali Berisha gives to “Edi Rama’s bandits”, or from cataloguing their luxury?

Today, there are no longer any naive people who believe that the Berisha family lives “like the middle class.” The doctor’s high-pitched voice cannot hide the luxury of his family, which in many cases directly competes with what he himself denounces from the headquarters of the Democratic Party. This makes moralizing not only powerless, but also unbelievable.

But the biggest problem is not this. The real problem is the spirit that the opposition is conveying. A public tired not only of the government's scandals, but also of the opposition's inability to inspire revolt, hope, or a real mechanism for overthrowing the government.

Neither the latest protest called by the DP, nor the sporadic protests of small parties are managing to channel the anger and despair of society. There is noise, but no direction. There are strong words, but no project.

The epithets that Sali Berisha gives Ergys Agas in press conferences, or the fragmentary "leaks" of the file in the media, are not enough to explain the real importance and the extraordinary damage that has been caused to the Albanian state and the security of citizens' data through the AKSHI.

Government scandals – from that of Deputy Prime Minister Balluku to the AKSH – are not overthrown by appeals, nor by a folklore of accusations. They are overthrown only when the opposition stops trivializing crime and starts treating it for what it is: an existential threat to the state and society.

Until then, press conferences will continue to look like today's: lots of noise, little meaning, zero change.

In the end, the government does not need to win elections or shut up. It is enough for scandal to turn into routine, truth into noise, and indignation into fatigue. When the opposition speaks as a spectacle and not as a conscience, crime no longer needs to be hidden. It simply continues.

And what is lost is not a government, but society's ability to recognize evil when it sees it.